Elevate your local knowledge

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

[byline]

Terry Chase was 54 years old when he met his biological father for the first time. He’d always known he was adopted and had been searching for his birth parents since he was a teenager.

But each time he tried to find out more information, the Penticton, B.C., man would come to a dead end.

That all changed in 2023, when his adoptive sister came up with an idea — she decided to post on Facebook about his search. Within two hours, Chase was connected with a man who appeared to be his biological father.

“The power of the internet, right? It’s crazy,” Chase told the IJF.

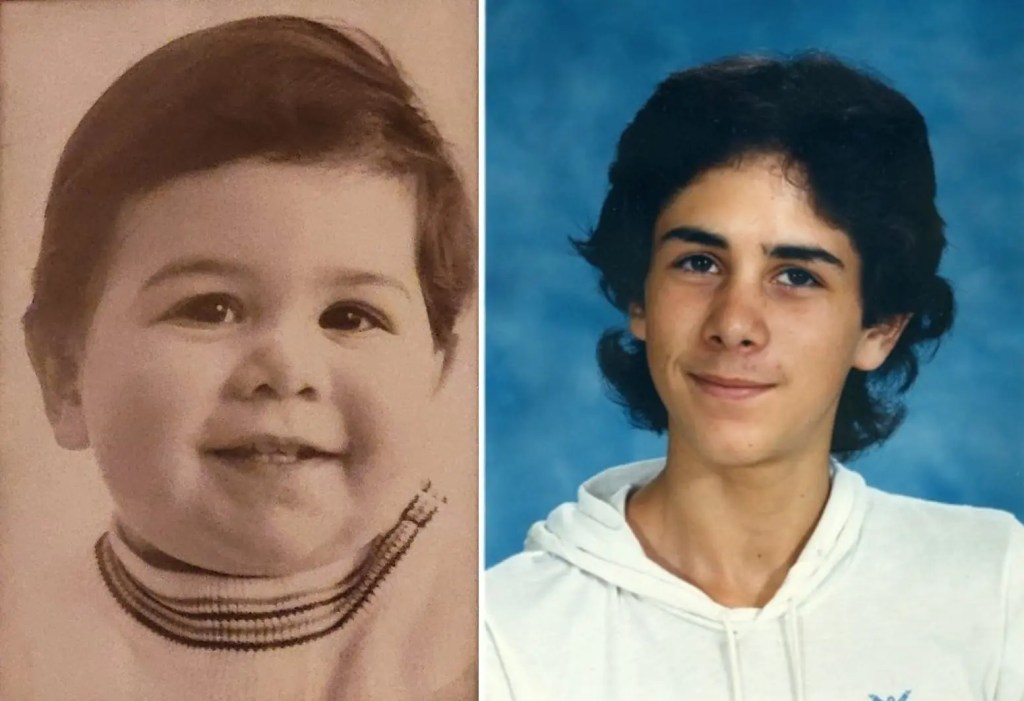

DNA testing would later confirm that his father was indeed Dorman “Dick” Joseph, a member of the Wei Wai Kum First Nation living in Campbell River, B.C. The family resemblance was striking.

“It was pretty obvious when you put the two pictures side by side,” Chase said. “The lady who did Dorman’s DNA test, she says … ‘Dorman, I don’t even need to do this test.’ She’s like, ‘That’s your son.’”

But with that happy discovery came much darker news, and Chase is still making sense of the events that led to his birth.

He learned he’d been conceived when Joseph was sexually assaulted at just 15 years old by a staff member at St. Michael’s Residential School in Alert Bay, B.C., in 1968. Joseph’s abuser was Jane Carol Peacock, a 21-year-old Englishwoman who’d been hired to work as a supervisor in the girls’ dorms.

This summer, father and son filed suit against the federal government, the Anglican Church and the B.C. diocese, holding them responsible for Peacock’s actions, which caused lasting psychological harm. Learning he’d fathered a son through the assault opened old wounds for Joseph, the claim says, and Chase was traumatized by the revelations.

“Mr. Chase is not just a consequence of the sexual assault, but also very much a victim of the sexual assault that took place at St. Mike’s,” they write in the claim.

Chase said hearing what his biological mother did to his father was very difficult.

“I found it very distracting at work and at home,” he said. “A lot of ‘what ifs’ and a lot of questions going on in my head.”

The government and the church bodies all admit that Peacock sexually assaulted Joseph. The problem, they allege in their responses to the claim, is that Joseph and Chase are legally barred from suing over it.

That’s because in 2008, Joseph settled a previous lawsuit he’d filed about the sexual assault. As part of the settlement, he signed a release covering all allegations of abuse related to his time at St. Michael’s.

“The individual release was drafted with broad language to include any and all potential claims against Canada stemming from Mr. Joseph’s time as a student at St. Michael’s Indian Residential School. This includes the possibility of any offspring resultant of the alleged abuse,” a response filed by Canada’s attorney general maintains.

Joseph and Chase’s claim argues the release should not absolve the church and government from liability for circumstances Joseph wasn’t even aware of at the time he signed it. However, the government’s response points out that Peacock informed Joseph she was pregnant and was planning to have an abortion, but he didn’t confirm she’d gone through with it.

The two men’s lawyer, Karim Ramji, told the IJF that the responses from the government and the church suggest a gap between their public commitments to reconciliation and their treatment of survivors.

“You’ve got two people here that are impacted by the residential school system. They’re connected in a huge way, and disconnected in a huge way. So what do we do to try to address this and deal with it?” he said.

Jennifer Cooper, a spokesperson for Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, said she couldn’t comment while the case is before the courts. But, she added in an email, “the Government of Canada approaches litigation related to past harms suffered by Indigenous people in a respectful, compassionate and fair manner.”

Representatives of the Anglican Church in B.C. and Canada have not responded to requests for comment.

‘You got punished for any little thing’

Joseph has spent most of his adult life as a fishing boat captain, but plans to retire soon. He also teaches the Kwakʼwala language and is an accomplished wood carver.

He spent his early childhood years on Turnour Island, off the east coast of Vancouver Island, where he learned to fish with his father and grandfather.

“My mother, my dad, my granny, my grandpa, my uncles, everybody — they were wealthy people. My grandfather owned a store in the village. But then they dragged us away from there and put us into Alert Bay,” Joseph recalled.

St. Michael’s Indian Residential School operated in Alert Bay from 1878 until 1974, and school narratives in the IJF’s residential schools database paint a picture of abuse, malnutrition and poor sanitation throughout its operation.

“It was a tough place to be. Everything was pretty strict, and you got punished for any little thing that you do, so a lot of people would want to try to run away. But you couldn’t run away from Alert Bay because it’s an island,” Joseph said.

He was forced to attend beginning in 1963, and described the experience as something like a prison camp.

That December, a school superintendent visited St. Michael’s and wrote a report about an incident where four girls and nine boys had been punished for sneaking into each other’s dorms on a Sunday night as part of a “childish pre-Christmas prank,” according to records in the IJF’s database.

During the Monday morning assembly, with the entire staff and student body as witnesses, the principal whipped the 14 children with a leather strap “about 18” long, 2” wide and ¼” thick,” and threatened to revoke Christmas holiday privileges for the entire school.

“This incident could have its serious repercussions and I do think the incident could have been handled in a less violent manner,” the superintendent wrote in his report.

Joseph is mentioned by name at least three times in the school narrative documents, and these records make it clear he was a boy with a lot of promise.

He was one of the top scorers in the finals of the 1968 broomball league, according to a report in the school newspaper from May of that year. The same publication notes that he was named a student monitor for the senior boys’ dorm, earning privileges like a monthly allowance of up to $10 and the right to stay up an extra half hour at night.

Even the local newspaper, the North Island Gazette, took note of Joseph’s talents. He was named in a short article from 1968 about young wood carvers who were learning the art form thanks to Joseph’s father, Harry, a St. Michael’s alumnus who went on to work at the school.

Joseph said finding hobbies to occupy his time was crucial to surviving St. Michael’s.

“They were all pretty aggressive there. We all had to find something to do. I always wanted to make sure I was doing something,” he said.

The carving room is one place where Joseph crossed paths with his abuser. The Gazette article mentions Peacock as one of two staff members who helped the students paint the walls with “huge Indian designs.”

Joseph remembers her watching him paint.

“Every time I turned she was right there. She was never far away,” he said. He had the same experience when he operated the projector for school movie nights.

“Jane was always around, right? Whatever I was doing, she was right there.”

The search for Jane Peacock

Joseph said he kept the assault secret from his family. But he received a letter from Peacock after she left St. Michael’s, informing him of her pregnancy and planned abortion.

“It blew me away. … I was probably 15 at the time,” he said. “But I made sure my sister read it too, so I had some kind of proof.”

Peacock is still believed to be alive somewhere, but Ramji said no one has been able to track her down. The IJF has also been unable to locate her. If she’s found, Joseph and Chase plan to add her as a respondent to their lawsuit.

During his long search for his biological parents, Chase connected with a group that helps adoptees find loopholes in closed adoptions. Within a day, they’d tracked down Peacock’s name.

Chase later obtained his original birth certificate and adoption papers.These records show that Peacock falsely reported the father of the child as 18 years old — three years older than Joseph’s age when she assaulted him. She also claimed he had wanted to marry her, but she refused.

Chase has tried to find Peacock in the past.

“I went by the last known address that she had, and I actually wrote her a letter, which I mailed off. Three months later, I got it back, saying that there was no Jane Peacock at that address,” he said.

He also identified a cousin from Peacock’s side of the family, and they exchanged a few messages, but the cousin eventually said they’d been told not to share any information about Chase’s biological mother.

He’s stopped trying to track her down since learning the circumstances of his birth.

After several trips to visit his biological family over the years, Chase said the situation has become easier to process, despite lots of “ups and downs.”

Today, he feels grateful for the new members of his family and tries “not to think about it too much.”

One of the silver linings is the sense of cultural identity and newfound family he has gained.

Chase attended his first potlatch in September, a West Coast First Nations feasting and cultural event that commemorates milestones like births, marriages and deaths. The potlatch was for a relative who had passed away.

“I’ve never experienced something like that before. It’s something I’ll never forget.” Chase said.

He said the day was filled with feasts, drumming, dancing and singing.

“I was just blown away.”

Chase said this experience has taught him the importance of widespread education about what happened at residential schools in Canada.

“You know with residential schools, you don’t learn a whole lot about it. I haven’t, until just recently — just started reading more books and looking stuff up.” He said.

His message for other children of survivors that are trying to learn more about their lineage, whether they are adopted or not is “don’t give up, always look.”

“It’s been amazing. It’s been eye-opening. I’m trying to be like a sponge and soak it all in, learning little bits here and there,” he said, reflecting on his growing connection to his culture and traditions.

Joseph couldn’t agree more.

“I’m very happy that Terry is a part of us. It took him a long time to find us,” he said.

A Residential Schools Crisis Line (1-866-925-4419) is available 24 hours a day for anyone seeking emotional support as a result of their residential school experience.

— This story was originally published by the Investigative Journalism Foundation. Ninah Hermiston and Rochelle Becker contributed.

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.