Imax film ‘Island of Lemurs’ focuses on rare resilient creatures on Madagascar

TORONTO – As if on cue, the massive whale emerged from the ocean to soar into the air and flip dramatically onto its back, spraying a tiny island as it sank again beneath the waves.

It was a rare moment of serendipitous filmmaking in the wild — one that director/cinematographer David Douglas still marvels at as his film “Island of Lemurs: Madagascar” is about to hit Imax theatres this weekend.

The Vancouver Island-based filmmaker jokes that the spectacular display was due to a “mental message” he sent the majestic beast, which managed to perfectly enact an imagined scene he had sketched out on paper before shooting.

“We knew where the whales were, the whole plan was to do that, but we never expected it would happen,” Douglas says during a recent promotional stop in Toronto.

“It was one of those things where we thought, ‘Oh, we want to do this sequence and the idea would be if it all just happened in one frame. But if we have to, we can cut it together.’ But we just went out there and on the first day we got the shot.

“And then for the next couple of days we tried to do better and we never did better.”

In addition to breaching whales, Douglas captures stunning images of spiny limestone pinnacles, craggy rock formations, ancient rainforests and, of course, an array of mischievous lemurs. They include the extremely rare greater bamboo lemurs — numbering only 300 in the world — as well as the dancing sifakas, the wailing indri and the famous ring-tailed variety.

Helping him track the sometimes hard-to-find primates was primatologist Patricia Wright, who has dedicated her life to protecting their fragile ecosystem in Madagascar. He also relied on local spotters to find a particular animal and stick with them until the crew was ready to shoot — in some cases weeks or months.

Douglas notes that some species have dwindled to dangerous levels, and his film documents local slash-and-burn agriculture practices that have destroyed large swaths of habitat.

“Some of the populations are in desperate trouble, some of them are just in trouble, some of them are maybe OK,” he says.

“There are no great stories, they all need help and for some there’s only a few hundred individuals left.”

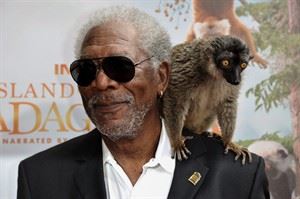

Douglas reteams with writer/producer Drew Fellman and Oscar-winning actor Morgan Freeman as narrator. The trio last worked together on the Imax 3D documentary “Born to Be Wild,” about orphaned animals, when Douglas served as director of photography.

Freeman’s high-wattage star power has brought much-needed attention to lower-profile nature films, he says.

“He’s really interested in conservation causes, too,” he says of the “Million Dollar Baby” star, also famous for lending his distinctive voice to the Oscar-winning documentary “March of the Penguins.”

“It’s been a tremendous boost to this process that he’s lent his talents to telling these stories.”

Being able to document the intimate lives of rare species is a passion for Douglas, who began his filmmaking career in high school when he met Imax inventors including Robert Kerr, Bill Shaw and Graeme Ferguson.

The 60-year-old notes “Island of Lemurs” uses a newly designed digital 3D camera equipped with remote sensor technology. That allowed crew members to chase the quick-moving creatures up into their tree-top homes.

“You can get very close, it’s quiet — the other cameras made noise — it never runs out of film … and it’s extremely variable in its frame rate so it can shoot any slow motion which we really couldn’t do with the film cameras,” says Douglas, who has photographed more than 30 films for Imax and other clients including the Imax docs “Fires of Kuwait” and the concert film “Rolling Stones: At the MAX.”

“That just means that we can suddenly use content to drive these stories, not just: What shot could you get with that animal before it ran over the hill? It’s really (about): What’s the behaviour of the animal? How are we in relation to it? And what kind of emotional story can we involve ourselves in with this creature in front of us?

“It begins to do justice to the complexity of the life of those animals because they live complex lives. They’re primates, they have relationships, they can plan for the future, they do a lot of things that we never give animals credit for, unless it was our dog, and so I think that’s what makes me feel good — is to see people responding, watching animals in sort of a more captivated way than maybe I’ve seen in the past.”

Friendly lemurs were not shy when the crew was around, Douglas adds. The cheeky animals would routinely walk near them, even jumping up to perch on a willing shoulder.

The Edmonton-born Douglas, who grew up in southern Ontario, says he’s optimistic about their future, even with all the threats that face their survival.

He thinks back to the moment lemurs are believed to have arrived on Madagasar millions of years ago as castaways from Africa. It’s widely held that a small group of “proto-lemurs” were washed out to sea in a storm and drifted to the island on a patch of vegetation.

Douglas imagines three-foot swells tossed their precarious floating raft to-and-fro while massive whales swam by, waving and breaching as they passed.

“There’s debate whether or not a few hundred individuals is enough to preserve a species but my answer to that is always: It was just one tree that drifted onto Madagascar’s beaches,” says Douglas, who now has his eye on following bears in the United States and China.

“So they’ll take care of themselves if we can leave them alone or give them a little bit of space. They’ll come back.”

“Island of Lemurs: Madagascar” opens Friday in select cities including Edmonton, Quebec City, Sudbury and Regina.

Join the Conversation!

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.