New doc ‘Jodorowsky’s Dune’ examines the ‘most influential film never made’

TORONTO – Frank Pavich discovered the work of surrealistic Chilean filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky through bootleg VHS cassettes, battered documents passed between friends.

At the time, Jodorowsky’s work — 1971’s bizarre, ultraviolent Western “El Topo” and his even-stranger follow-up, 1973’s “The Holy Mountain” — was subject to a three-decade embargo due to a conflict with the film’s distributor. To Pavich, the inaccessibility of Jodorowsky’s work — in both the literal and figurative sense — only sharpened his fascination.

“Who was this weird director who made these amazing movies we were forced to watch on multi-generational VHS tapes?” Pavich said in a recent telephone interview from Hong Kong. “You watched these movies, you didn’t know where the hell they were from. This was before the Internet, so you couldn’t research him. You had no idea what the story was, the story of the films or the guy who made them.

“And then to kind of learn there was this lost film, his follow-up to ‘Holy Mountain’ — which is one of the most bizarre and most amazing films ever — there was this follow-up film that never happened. … It just (seemed) it was meant to have its story told to everybody.”

The lost film in question was Jodorowsky’s sprawling, ludicrously ambitious adaptation of Frank Herbert’s reputedly unfilmable sci-fi epic “Dune.” And his ultimately unsuccessful quest to make that film — using some of the biggest creative luminaries in the world — is captured in Pavich’s second feature documentary, “Jodorowsky’s Dune,” which opens Friday in select theatres in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver.

A making-of special for a movie that was never made, Pavich’s film wouldn’t have been successful without a compelling central character. So when he traipsed out to Jodorowsky’s Paris apartment for their first interview session, he knew the result would be crucial.

After a two-hour sit-down, Pavich vividly recalls packing up and turning to his crew.

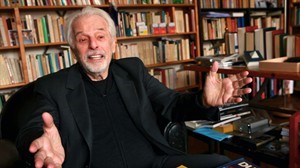

“We just stopped and looked at each other like, ‘Holy crap. Can you believe what we just captured?’” Pavich recalled. “He’s 85 now but he comes across like a man half his age. Completely alive. His eyes are alive and sparkly and he’s hilarious and moving and touching and deep and really, everything.”

Indeed, Jodorowsky is as entertaining a narrator as one could imagine. Without a trace of bitterness, the visionary artist details his mid-70s plan to turn “Dune” into what he wanted to be the filmic equivalent of an LSD trip.

He somehow successfully recruited Orson Welles, Mick Jagger and Salvador Dali for roles in his epic. He persuaded Pink Floyd to provide the music. His film was to be somewhere between 12 and 20 hours.

He never actually bothered to read Herbert’s book before embarking on this plan, mind you. As the gregarious director explains in the film with typically wide-eyed glee: “I was raping Frank Herbert … but with love, with love.”

With an endlessly expressive face and outsized ego, Jodorowsky is not only compelling to watch as he unfolds his story — he’s hilarious, and seemingly not always intentionally. During screenings at last year’s Toronto International Film Festival, the freewheeling “Jodorowsky’s Dune” inspired peals of laughter at moments when Jodorowsky’s self-awareness seemed to ebb.

Although Pavich has deep respect for his subject, he says he has hours of extra footage of the self-proclaimed “psychomagician” that he “could just watch all the time.”

“(It) should be seen by everybody,” he says with a chuckle. “You can only imagine what he says. Oh my God. It’s shocking. It’s incredible.”

But Jodorowsky’s film wasn’t the spectacular folly one might think. He recruited writer Dan O’Bannon, Swiss artist H.R. Giger and French artist Jean Giraud (known under the pseudonym Moebius) to help craft his vision, a highly respected team who would go on to collect credits in some of the biggest sci-fi films of the past 40 years.

Together, they assembled an intricately detailed book of storyboards and designs for Jodorowsky’s “Dune,” which are recreated in Pavich’s film and brought to life in inventive animated sequences.

Although Jodorowsky failed to round up the necessary funding to film his vision — which would have cost about $15 million — his “book” exactly mapped out his vision for “Dune.” And so, Pavich believes, Jodorowsky did make his movie, even if not in the format he originally wanted.

“Going in, you think it’s going to be this story of this failure, because how could it not be a story of a failure? It’s about a movie that didn’t happen,” he said. “But in Jodorowsky’s hands and in his storytelling, it becomes the story of a great success — of one of the greatest successes.”

Of course, Pavich wasn’t alone in being influenced by Jodorowsky’s work.

With “El Topo,” he’s widely credited with creating the first midnight movie. John Lennon, Bob Dylan, Peter Gabriel, Peter Fonda, Gore Verbinski, Marilyn Manson and Dennis Hopper publicly pledged allegiance to his work at various points. Kanye West recently credited “The Holy Mountain” with inspiring the striking imagery of his “Yeezus” tour, reportedly telling a crowd at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center that “everybody copied off (Jodorowsky).”

And according to Pavich’s film, his “Dune” was perhaps just as influential despite never being made.

O’Bannon, Giger and Giraud formed the team that went on to make the deeply influential 1979 classic “Alien,” and that film’s unsettling visuals undeniably shared DNA with Jodorowsky’s planned “Dune.” Pavich’s film also convincingly draws parallels between “Dune” imagery and several other cinematic classics, including “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” “Blade Runner” and “Star Wars,” as well as more recent fare including “The Fifth Element” and “Prometheus.”

(Not to mention David Lynch’s ultimately doomed 1984 version of “Dune,” which in the film Jodorowsky pronounces “awful” with palpable glee.)

“It’s definitely the most influential film never made, for sure,” Pavich said of Jodorowsky’s epic.

Pavich sat with Jodorowsky when they watched his documentary for the first time at Cannes, with Jodorowsky’s wife sitting between the directors “as a little buffer in case the movie was bad,” he posits.

It wasn’t necessary, although the viewing experience, Pavich believes, was “overwhelming” for Jodorowsky.

“Towards the end of the film, I could see that he and his wife were wiping tears away,” he said. “Once the credits had rolled, I just leaned forward and said, ‘what did you think?’ And he just turned to me and said: ‘It’s perfect.’”

By participating in Pavich’s documentary, Jodorowsky was reunited with his old producer, Michel Seydoux. The two had spent the decades since their frustrating “Dune” experience both presuming that the other held hard feelings, Pavich explained. Realizing recently that that wasn’t the case, they came together to collaborate on Jodorowsky’s first new film in 23 years, “The Dance of Reality.”

The dreamy film, about the director’s unhappy childhood, has been screening at many of the same film festivals as “Jodorowsky’s Dune” and receiving warm reviews.

Pavich, meanwhile, is unsure of his next move. He feels he has a high standard to which to aspire.

“The only thing I know about the next film is that it really needs to be something that would make (Jodorowsky) proud,” he said. “He gave me that story to tell. He didn’t have to. He could have said no and turned me away.

“I certainly wouldn’t want to do anything that would make him regret giving me that gift,” he added. “I know that he loves ‘Jodorowsky’s Dune’ a lot and he says it’s very artistic. I hope I can make something else (like that) — and that doesn’t mean to make a Jodorowsky film. I don’t need to have pelicans walking around with hippopotamuses and stuff. But something with a deeper meaning, that his films always carry, I think that’s the goal.

“The challenge is on.”

___

Follow @CP_Patch on Twitter.

Join the Conversation!

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.