Trump wants to end temporary protection for over a million immigrants. What does that mean?

Millions of people, many from troubled nations, live legally in the United States under various forms of temporary legal protection. Many have been targeted in the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown.

On Monday, the Supreme Court allowed the administration to end protections that had allowed some 350,000 Venezuelan immigrants to remain in the United States. That group of Venezuelans could face deportation.

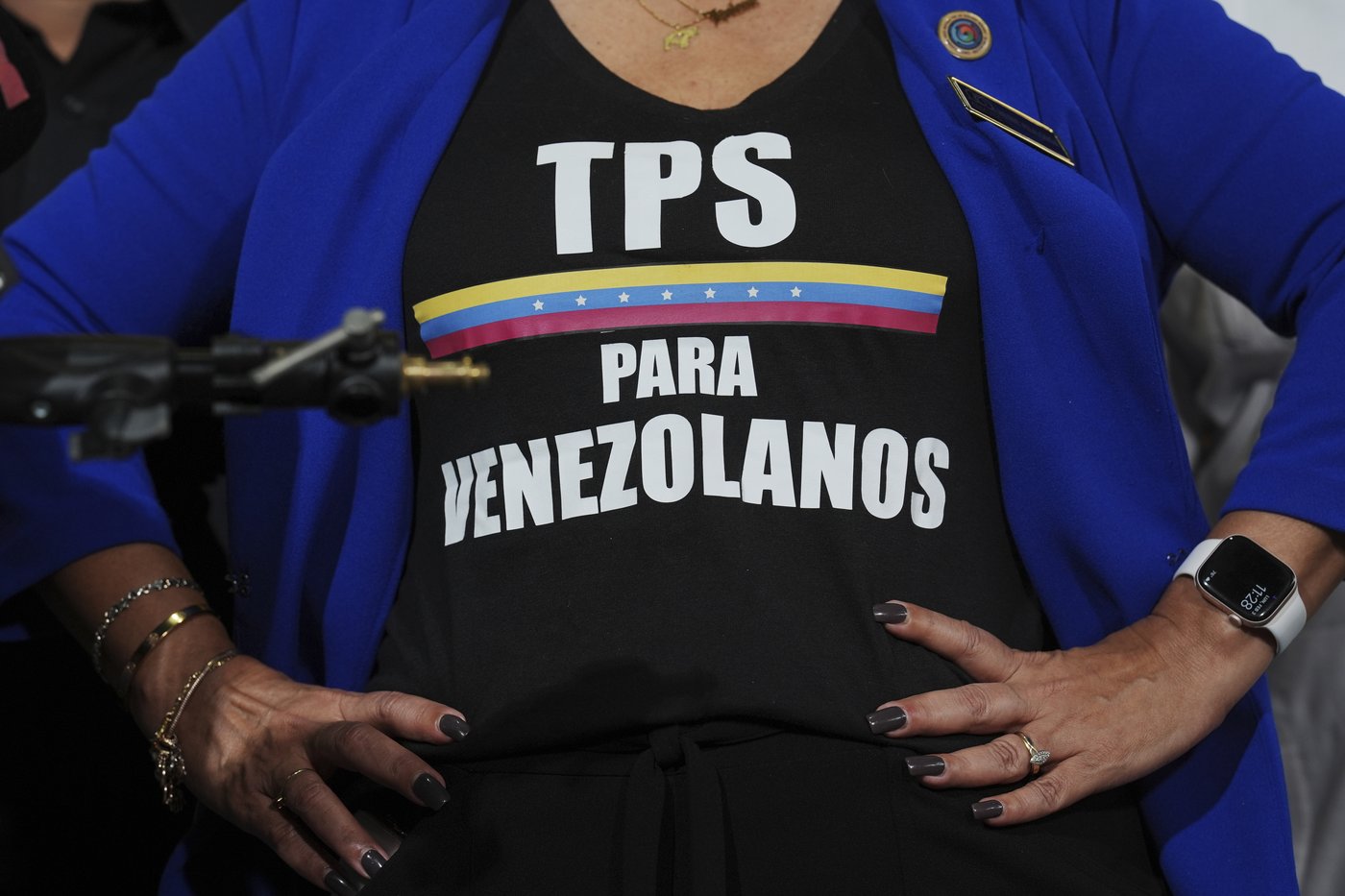

The Venezuelans had a form of protection known as Temporary Protected Status. Administration officials had ordered TPS to expire for those Venezuelans in April. The Supreme Court lifted a federal judge’s ruling that had paused the administration’s plans.

Here’s what to know about TPS and some other temporary protections for immigrants:

Temporary Protected Status

Temporary Protected Status allows people already living in the United States to stay and work legally for up to 18 months if their homelands are unsafe because of civil unrest or natural disasters.

The Biden administration dramatically expanded the designation. It covers people from more than a dozen countries, though the largest numbers come from Venezuela and Haiti.

The status doesn’t put immigrants on a long-term path to citizenship and can be repeatedly renewed. Critics say renewal had become effectively automatic for many immigrants, no matter what was happening in their home country.

Temporary Protected Status covered the 350,000 Venezuelans affected by Monday’s Supreme Court decision. An additional 250,000 Venezuelans covered by an earlier TPS designation are set to lose those protections in September.

The administration also is ending the designation for roughly half a million Haitians in August.

Humanitarian parole

More than 500,000 people from what are sometimes called the CHNV countries — Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela — live in the U.S. under the legal tool known as humanitarian parole.

To qualify, they had to fly to the U.S. at their own expense and have a financial sponsor. They could not enter the U.S. through the border with Mexico. For most people, the designation lasts for two years.

Last week, the administration asked the Supreme Court to allow it to end parole for immigrants from those four countries. The emergency appeal said a lower-court order had wrongly encroached on the authority of the Department of Homeland Security.

U.S. administrations – both Republican and Democratic – have used parole for decades for people unable to use regular immigration channels, whether because of time pressure or bad relations between their country and the U.S.

The program is unrelated to parole in the criminal justice system.

CBP One

In a separate parole program, more than 900,000 immigrants were temporarily allowed into the U.S. during the Biden administration using the CBP One app, which brought a degree of order to the southern border as illegal immigration surged. The app, effectively a type of lottery, allowed a limited number of people every day to set up appointments at U.S. border crossings.

People who entered using CBP One were typically given two years to live and work in the U.S.

Shortly after Trump was sworn in, the administration abruptly ended the use of CBP One, and canceled tens of thousands of existing appointments.

In April, some immigrants who had used the app to enter the U.S. were told in emails to leave the country “immediately.”

“Do not attempt to remain in the United States — the federal government will find you,” it said.

It is unclear how many people were sent the message or when they must leave. Immigrant rights groups are challenging the administration’s orders for immigrants to self-deport.

Join the Conversation!

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.