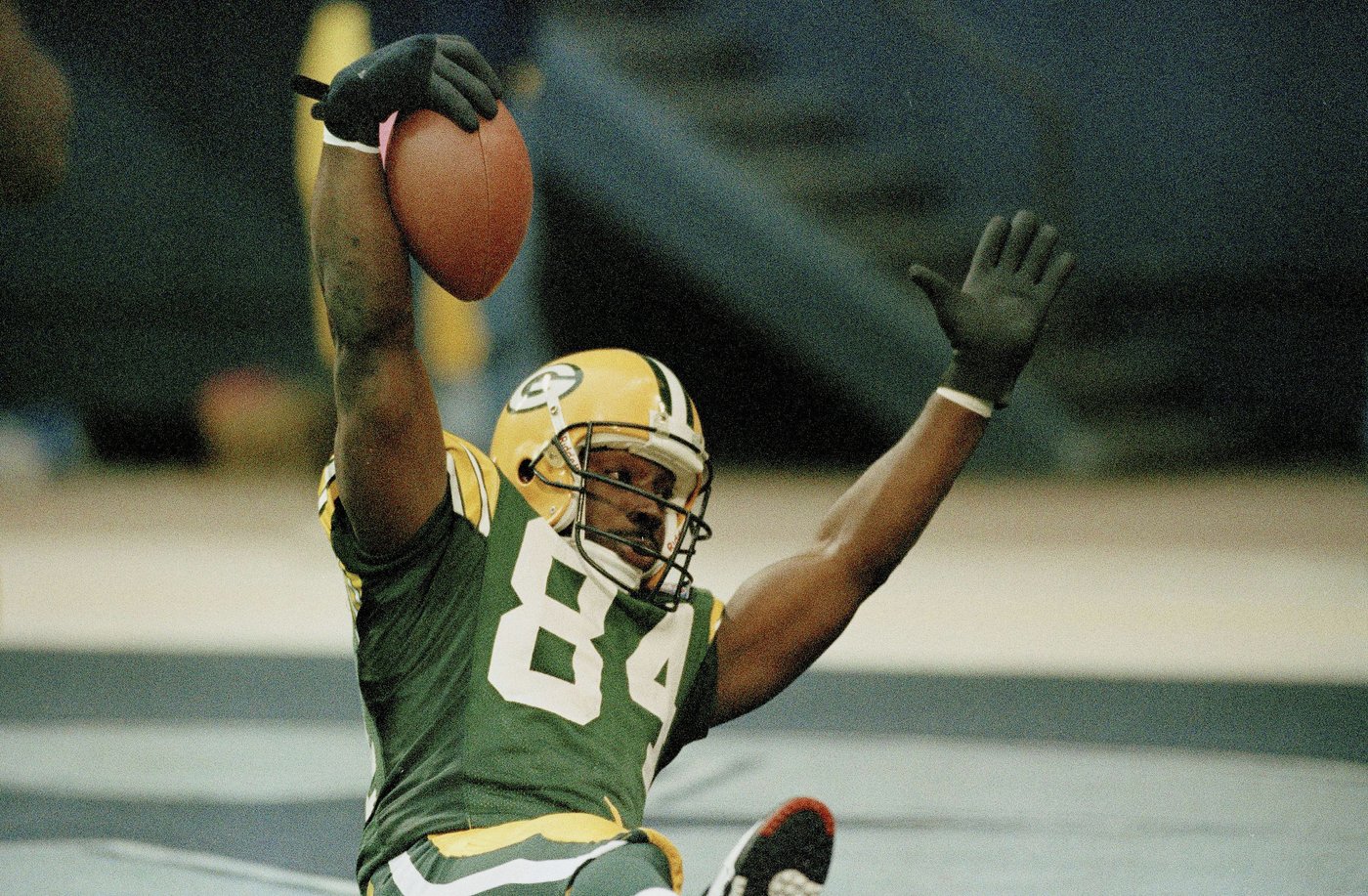

Ex-Packers receiving great Sterling Sharpe joins tight end Shannon as first brothers in Hall of Fame

Shannon Sharpe donned his gold jacket emblazoned with the Pro Football Hall of Fame logo at his Atlanta home last winter and awaited his brother’s arrival.

Sterling ambled down the stairs and into the basement looking perplexed.

“Welcome, bro!” Shannon said.

To what, Sterling wondered, “your house?”

“To the Pro Football Hall of Fame,” corrected Shannon. “Class of 2025.”

The first pair of brothers who will ever have both of their busts on display in Canton fell into each other’s arms, decades of doubts dissipating in a medley of laughter and tears.

Dashed was the notion that seven stellar NFL seasons weren’t enough for football immortality.

All along, the brothers figured it was Sterling who would reach Canton first. He was born three years earlier and the wide receiver had a standout career at South Carolina and then for the Green Bay Packers, who made him a first-round pick in 1988, two years before the Denver Broncos selected his younger brother in the seventh round out of Savannah State.

Sterling would start every game for seven straight seasons until a neck injury cut short his career just as he and the Packers were peaking. The green and gold would go on to return the title to Titletown behind fellow Hall of Famers Ron Wolf, LeRoy Butler, Reggie White and Brett Favre while Sterling dabbled in broadcasting before leaving football behind for the golf links.

Sterling was named to five Pro Bowls and earned first-team All-Pro honors the three years he led the league in receptions. He averaged 85 catches in his career — an unheard of number for that era and 10 more than Jerry Rice averaged in his first seven seasons.

In his last season he led the league with 18 touchdown receptions, including a trio of scores in his final game despite dealing with numbness in his arms and tingling in his neck caused by an abnormal loosening of the first and second vertebrae in his cervical spine.

He had felt increasingly bothersome symptoms over the last half of that season and he suffered what’s commonly referred to as “stingers” against the Falcons in the Packers’ final game at the old Milwaukee County Stadium on Dec. 18, 1994, and again six days later at Tampa, where he caught nine passes for 132 yards and three first-half touchdowns in what turned out to be his final game.

Right after Christmas, he learned he needed neck fusion surgery that would limit his head swivel, making it too dangerous to continue playing football. Upon hearing the prognosis, he stood up and shook his doctors’ hands.

“I had already accomplished what I wanted to,” Sterling told NBC affiliate WIS News in Columbia, South Carolina, this spring. “… I just wanted to play, and I got to play in the NFL for seven years.”

His career cut short at age 29, his protracted wait for Canton would last 31 years.

“Sterling was supposed to be in the Hall first,″ Shannon said ahead of his 2011 induction, where he drew a standing ovation for saying, ”I’m the second-best player in my own family.”

Unlike Sterling’s truncated testimonial, Shannon’s Canton credentials were never in question. He set the standard at tight end, going to eight Pro Bowls in 14 seasons, earning four first-team All-Pro honors and winning three Super Bowls in a four-year span, two in Denver and one in Baltimore.

He gave his first Super Bowl ring — from Denver’s 31-24 win over Green Bay in 1997 — to Sterling. And he called the chance to welcome his big brother into the Hall “the proudest moment of my life.”

Despite their shared love of the game, the brothers who grew up in a tiny cinder block house in rural Georgia were different in one big way: Shannon overcame a childhood speech impediment to become one of the game’s most talkative players and later one of football’s most vocal commentators. Sterling preferred to hone his craft in relative obscurity and mostly avoided the public and the media.

“As a football player, I was unapproachable,” Sterling told WIS News. “I didn’t want to be approached. I didn’t want to be famous. I didn’t want to make friends. I’ve got a job to do and I’m going to do this job better than anyone else does anything else.”

Butler said Sterling’s media blackout was on par with his isolated nature. He just didn’t let many people into his orbit.

“Sterling didn’t want nobody to know what he did,” Butler told The Associated Press. “He didn’t want other receivers mimicking him. His edge was his physicality and his brain.”

Butler said teammates started calling Sterling “The Hermit,” because “he just wanted to play football. He didn’t want to go nowhere. He didn’t want to do nothing. He’d be swiping his card to get into (Packers headquarters) at 6 o’clock when nobody’s up but burglars and roosters.”

Ask him for his autograph and he’d walk right past you. Send him a letter care of the Packers and he’s sign a stack of them, Butler said.

Every Tuesday, Sterling would spend his time answering fan mail, “signing 1,000 autographs,” Butler said. “I never did that. He was the only one in the building signing everything. He’s probably going to hate on me for telling that story.”

Sterling was amongst a group of wide receivers including Andre Reed and Jerry Rice that defenses began double-teaming in the late 1980s.

Sterling embraced the extra attention of the “clamp and vice” defense and actually became better for it.

“He said if two guys are doubling me, they don’t hide it,” Butler recounted. “The corner has outside leverage, the safety has inside leverage, the linebacker is in a zone. He broke it down like this: ‘When it’s a pass, I’m going to attack the worst cover guy, the safety. When it’s a run, I’m going to attack the worst tackler, the cornerback.‘ I’d never heard nothing like that. It made so much sense.

“If he’s putting pressure on the safety, running straight at him, it’s what we call a panic state. As soon as he turns around to run with you, you stop on a dime and ‘Magic’ (Don Majkowski) or Brett would throw him the ball. I’d never seen any receiver do that, where he just said I’m going to attack the weakest guy based on what the play is.”

Butler said another of Sterling’s hush-hush advantages actually salvaged his own career.

Favre’s fastballs at practice were exacerbated in the winter months, so to save his hands and preserve rhythm with his quarterback, Sterling began wearing scuba diving wetsuit gloves, Butler said. With their padding and super tack, the gloves served like a catcher’s mitt. They worked out so well in the elements that Sterling began wearing them indoors, too, Butler said.

“So I went out and got me some scuba gloves like Sterling and it saved my career,” Butler said. “I started to get more interceptions. And before you know it our whole secondary was wearing them. I don’t think opponents realized it. Again, you don’t talk about it.”

___

AP NFL: https://apnews.com/NFL

Join the Conversation!

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.