Elevate your local knowledge

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Selecting your primary region ensures you get the stories that matter to you first.

TAYBEH, West Bank (AP) — Early on Sundays, bells call the faithful to worship at the three churches in this hilltop village that the Gospel narrates Jesus visited. It is now the last entirely Christian one in the occupied West Bank.

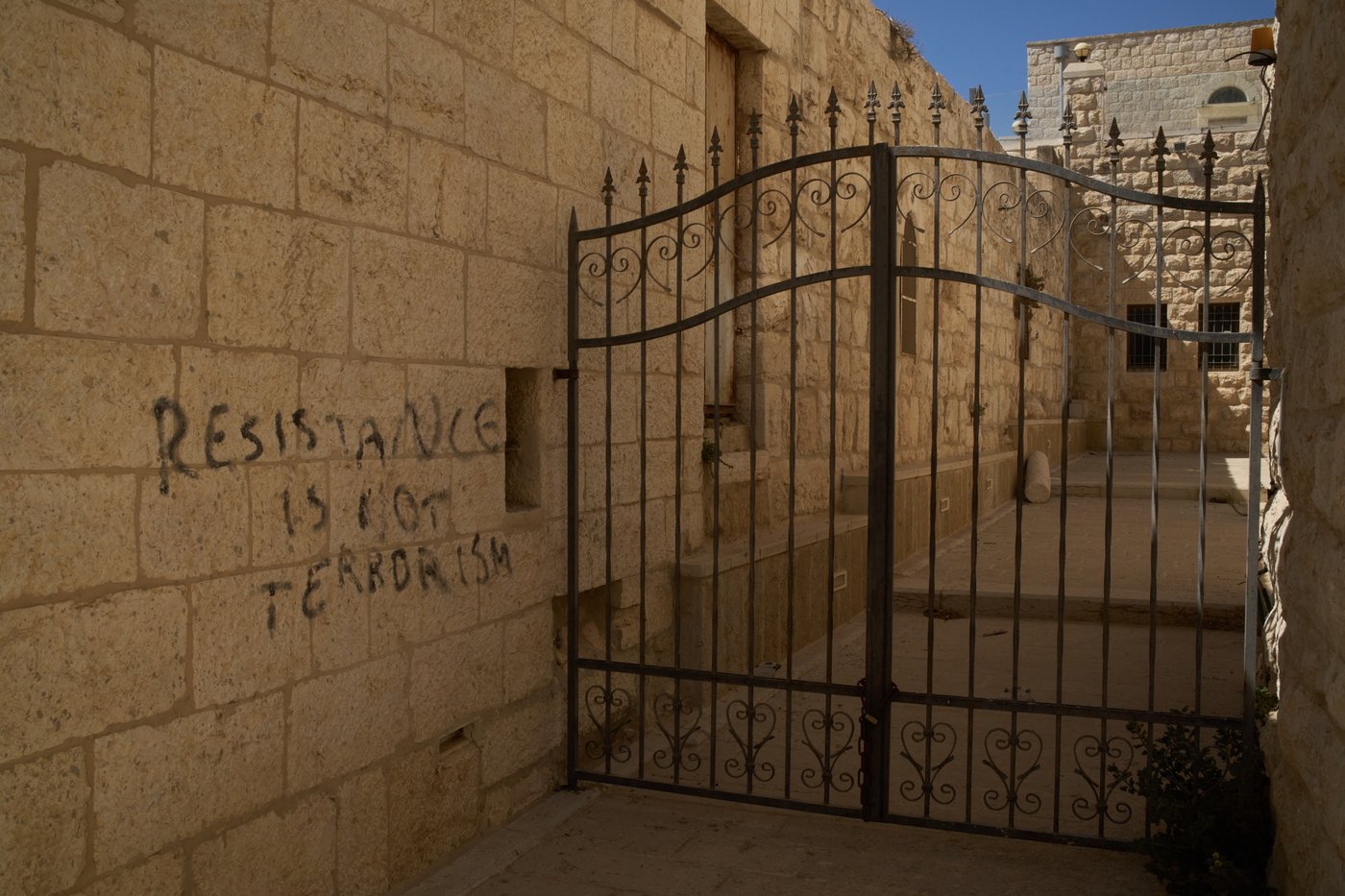

Proudly Palestinian, Taybeh’s Christians — Catholics of the Roman and Greek Melkite rites, and Greek Orthodox — long most for independence and peace for this part of the Holy Land.

But that hope feels increasingly remote as they struggle with the threats of violence from Jewish settlers and the intensifying restrictions on movement imposed by Israel. Many also say they fear Islamist radicalization will grow in the area as conflicts escalate across the region.

And even Thursday’s announcement of an agreement to pause fighting in Gaza didn’t assuage those urgent concerns.

“The situation in the West Bank, in my opinion, needs another agreement — to move away and expel the settlers from our lands,” the Rev. Bashar Fawadleh, parish priest of Christ the Redeemer Catholic Church, told The Associated Press. “We are so tired of this life.”

On a recent Sunday, families flocked to Mass at the church, where a Vatican and a Palestinian flag flank the altar, and a tall mosaic illustrates Jesus’ arrival in the village, then called Ephraim.

More families gathered at St. George Greek Orthodox Church. Filled with icons written in Arabic and Greek, it’s just down the street, overlooking hillside villas among olive trees.

“We’re struggling too much. We don’t see the light,” said its priest, the Rev. David Khoury. “We feel like we are in a big prison.”

A decades-old conflict spirals

The West Bank is the area between Israel and Jordan that Israel occupied in the 1967 war and that Palestinians want for a future state, together with east Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip. Israel seized them from Jordan and Egypt in that war.

The Israel-Hamas war that has devastated Gaza since Hamas-led militants attacked Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, has affected the strip’s tiny Christian community. The Catholic church was hit by an Israeli shell in July, though it’s functioning again.

Violence has also surged in the West Bank. Israeli military operations have grown to respond to what the army calls an increasing militant threat, most visible in frequent attacks at checkpoints.

Palestinians say uninvolved civilians have been caught up in the raids and blame the army for not defending them from near-daily violence by settlers.

After leading the music ministry at a recent Sunday’s Catholic Mass, as he’s done for six decades, Suheil Nazzal walked to the village’s edge to survey his terraces of olive trees.

Settlers no longer allow him and other villagers to harvest them, he said. He also blames the settlers on an opposite hilltop for setting a fire this summer that burned dangerously close to the cemetery where his parents are buried and to the ruins of Taybeh’s oldest church, the 5th-century St. George.

Christian families leaving the Holy Land

Nazzal plans to stay in Taybeh, but his family lives in the U.S. Clergy said at least a dozen families have left Taybeh, population 1,200, and more are considering leaving because of the violence, dwindling economy opportunities, and the way checkpoints restrict daily life.

Victor Barakat, a Catholic, and his wife Nadeen Khoury, who is Greek Orthodox, moved with their three children from Massachusetts to Taybeh, where Khoury grew up.

“We love Palestine,” she said after attending a service at St. George. “We wanted to raise the children here, to learn the culture, the language, family traditions.”

Yet while hoping they can stay in Taybeh, they say the security situation feels even more precarious than during the intifada, or Palestinian uprising, of the early 2000s, when hundreds of Israelis were killed, including in suicide bombings, and thousands of Palestinians were killed in Israeli military operations.

“Everyone is unsafe. You never know who’s going to stop you,” Barakat said, adding they no longer take the children to after-school activities because of the lack of protections on the roads.

And while he rejoiced for the agreement to pause fighting in Gaza, he doubted it would have an impact on settler attacks nearer home.

“The agenda for the West Bank is still more complicated,” Barakat said.

Taybeh’s Christian churches run schools, ranging from kindergarten to high school, as well as sports and music programs. The impact on young people of the current spiral of mistrust and violence is worrisome for educators.

“We don’t feel safe when we go from here to Ramallah or to any (village) in Palestine. Always there is a fear for us to be killed, to be … something terrible,” said Marina Marouf, vice principal at the Catholic school.

She said students have had to shelter at the school for hours waiting for the opening of “flying checkpoints” — road gates that Israeli authorities close, usually in response to attacks in the area.

Trying to keep the presence — and the faith

From villages like Taybeh to once popular, now struggling tourist destinations like Bethlehem, Christians account for between 1%-2% of the West Bank’s roughly 3 million residents, the vast majority Muslim. Across the wider Middle East, the Christian population has steadily declined as people have fled conflict and attacks.

But for many, maintaining a presence in the birthplace of Christianity is essential to identity and faith.

“I love my country because I love my Christ,” Fawadleh said. “My Christ is Ibn Al-Balad,” he added, using an Arabic term meaning “son of the land.”

Israel, whose founding declaration includes safeguarding freedom of religion and all holy places, sees itself as an island of religious tolerance in a volatile region. But some church authorities and monitoring groups have lamented a recent increase in anti-Christian sentiment and harassment, particularly in Jerusalem’s old city.

While those targeting Christians are a tiny minority of Jewish extremists, attacks such as spitting toward clergy are enough to create a sense of impunity and thus overall fear, said Hana Bendcowsky. She leads the Jerusalem Center for Jewish-Christian Relations of the Rossing Center for Education and Dialogue.

The Catholic Church’s Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, Cardinal Pierbattista Pizzaballa, has also highlighted growing problems in the West Bank, from settlers’ attacks to lack of jobs and of permits to move freely, adding that more Christians might decide to leave.

For the Franciscan priest who’s the new custodian of the Holy Land and oversees more than 300 friars in the region ministering to various holy sites, “the first big duty we have here is to stay.”

“We can’t stop the hemorrhage, but we will continue to be here and be alongside everyone,” said the Rev. Francesco Ielpo, whom Pope Leo XIV confirmed three months ago to the Holy Land mission established by St. Francis more than 800 years ago.

Struggling to provide hope among despair

Ielpo said the biggest challenge for Christians is to offer a different approach to social fractures deepened by the war in Gaza.

“Even where before there were relationships, opportunities for an encounter or even just for coexistence, now suspicions arise. ‘Can I trust the other? Am I really safe?’” he said.

Michael Hajjal worships at Taybeh’s Greek Orthodox church, and is torn between his love for the village, the constant fear he feels, and the concern for his son’s future.

“What kind of future can I create for my son while we’re under occupation and in this economic situation?” he said. “Even young people of 16 or 17 years old are saying, ‘I wish I were dead.’”

Hope — in addition to practical help ranging from youth programs to employment workshops — is what the clergy of Taybeh’s churches are working together to provide in the face of such despair.

“Still we are awaiting the third day as a Palestinian,” Fawadleh said. “The third day that means the new life, the freedom, the independence and the new salvation for our people.”

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.