Elevate your local knowledge

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Selecting your primary region ensures you get the stories that matter to you first.

Stuck on the side of Highway 3, George Bathgate had hitchhiked from Victoria to Charlottetown and back, but on a summer’s day in late August 1972, he was finding it surprisingly difficult to get a ride out of Christina Lake.

People were driving by slowly, very slowly, but no one was stopping.

It was 10 p.m., and Bathgate had been waiting three or four hours when an Old Dutch Potato Chip Truck pulled over. The driver told him to jump in the back, not the passenger seat.

The chip truck driver then told him that if he’d struggled to get a lift, it was because there was a murderer on the loose.

“My heart started to beat, I thought, ‘Oh no, is this the murderer… and I’m the next victim,'” Bathgate told iNFOnews.ca.

It was pitch black in the back of the chip truck, and Bathgate realized there was another person in the back. A little while later, it began slowing down.

“We’re in the middle of nowhere, and why is he pulling over?” Bathgate said.

Moments later, the door was pulled open and shotguns were pointed at them.

It was the RCMP and they were looking for a killer.

On Aug. 28, 1972, William Bernard Lepine, murdered six people in the South Okanagan and the Kootenays after he’d escaped from a psychiatric ward in Creston days earlier.

Stories from the Vancouver Sun say he was driven by a desire to save the world. Suffering from acute psychosis, Lepine believed there would be a nuclear holocaust on Labour Day, and that he had been chosen “in some special way” to save a group of disabled children.

On the morning of Aug. 28, 1972, he broke into a house near Oliver and stole guns and ammunition.

He then shot and killed 16-year-old Willard Lee Potter and 71-year-old Christopher Charles Wright at an orchard outside Oliver.

He travelled further, along the Highway and came to a campsite along the Kettle Valley River. A 1972 story from the Province called it the Damfino Creek Campsite, where he met Lester and Phyllis Clark, and Allan and Mildred Wilson.

He forced the two couples into a motorhome and began shooting. He killed 61-year-old Phyllis Clark in front of her husband and wounded the others before driving off.

Remarkably, while bleeding from gunshot wounds, the Wilsons got in their car and drove toward Westbridge for help. Lester Clark, who was also shot and injured, followed in the motorhome, his dead wife still in the vehicle.

The 27-year-old killer then travelled east and arrived in Edgewood, where he killed 57-year-old Herbert Evan Thomas and his 56-year-old wife Nellie. From there, he made his way to Nakusp and killed 24-year-old Thomas John Pozney, who was out fishing.

Newspaper reports don’t say how he was taken into custody, but the RCMP caught up with him in Nakusp.

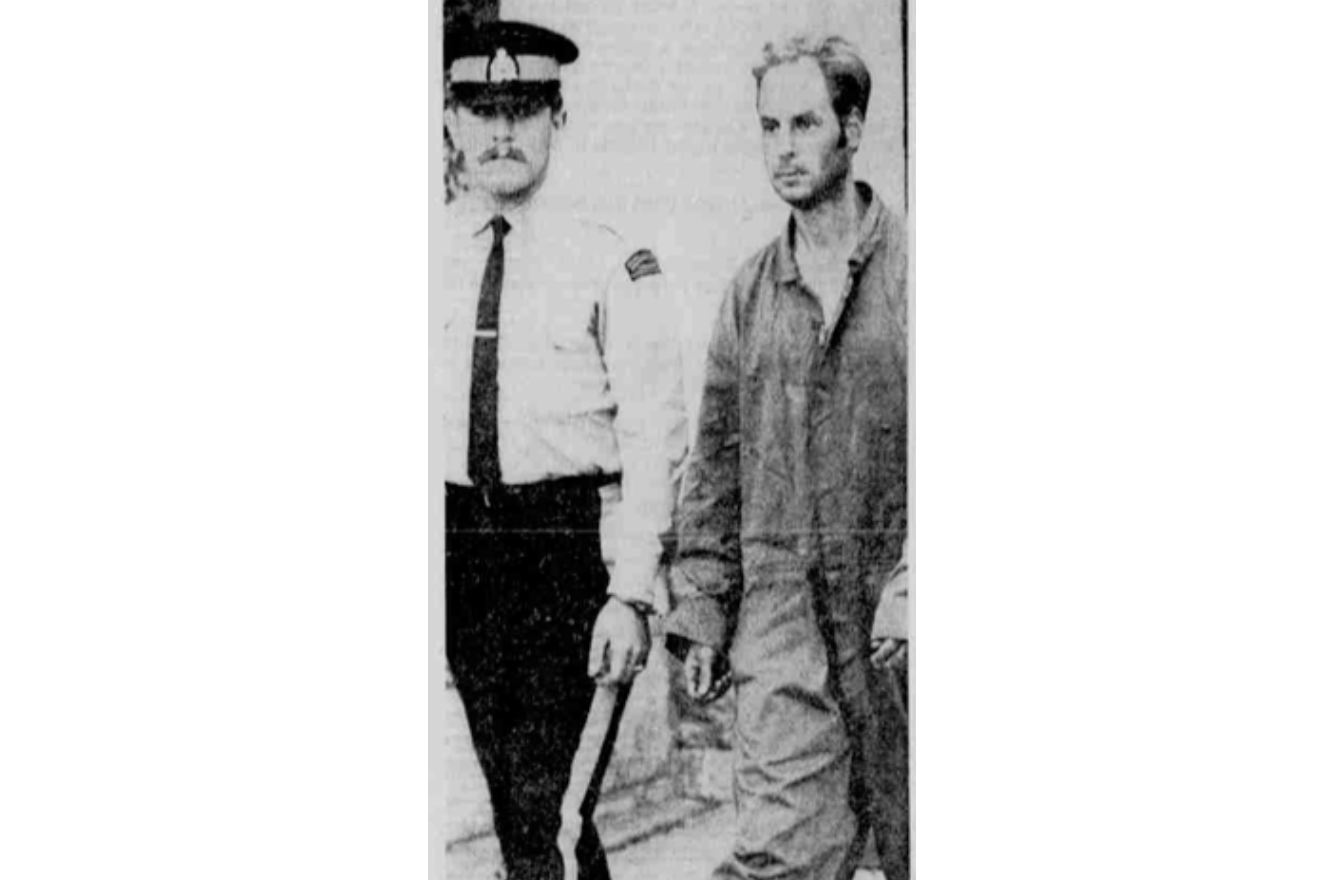

A psychiatrist evaluated Lepine in what he said was “the strictest security I have ever experienced… Lepine was stark naked and handcuffed with his arms behind his back.”

In 1974, a provincial court jury found him not guilty by reason of insanity, and he was placed in a psychiatric facility.

Earlier this month, the BC Review Board published its latest decision ruling again that the now 80-year-old remain in custody.

“Despite continuous hospitalization… since his not guilty by reason of insanity verdict, Mr. Lepine has remained profoundly mentally ill with no insight into his illness and has maintained that his actions at the time of the… offence were justified,” the March 3 BC Review Board decision reads. “The Board heard that Mr. Lepine remained chronically psychotic and delusional and had no insight into his mental illness or his need for treatment.”

Little is known about who Lepine is, only that he was an American who had been living in the Kootenays at the time. An article in the Province, written a month after the killings, said he may have been a draft dodger and was a loner.

“He never mentioned anything about his family or where he was from. He seemed to be on the defensive with everything bottled up inside,” Anglican minister Rev. Norman Tannar told the Province about a time Lepine had come over to see him. “Most of our conversation, then and on other occasions, seemed to drift off into vague philosophical and religious fields. He surprised me once, however, by getting very upset over the fact that the word ‘mission’ doesn’t appear in the Bible.”

Newspaper articles say he worked in orchards around the Okanagan and spent time in Summerland. In the summer of 1971, he was working in Creston doing gardening and maintenance jobs for the municipality.

In 1972, he was hired by the Dr. Endicott Home School and Work Centre, which was an institution for disabled children. The name of the provincial department that funded the centre is highly offensive in today’s terms.

“He did well at first and was very conscientious and dependable,” the director of the home told The Province.

However, things changed, and he was later fired for taking a work vehicle without permission.

One staff member said that after knowing him for three months, she began to believe he was dangerous.

“I heard from other members of the staff that Bill wanted to take the kids out of the home, and he was talking about nuclear war coming,” the staff member said.

Not long afterwards, he was hospitalized in Cranbrook.

“It was clear that he was psychotic at that time, but there was no evidence that he was a threat to anyone,” the director of East Kootenay Mental Health Unit told the paper. “He felt he had to save the children of the Dr. Endicott Home from the nuclear war that was on its way.”

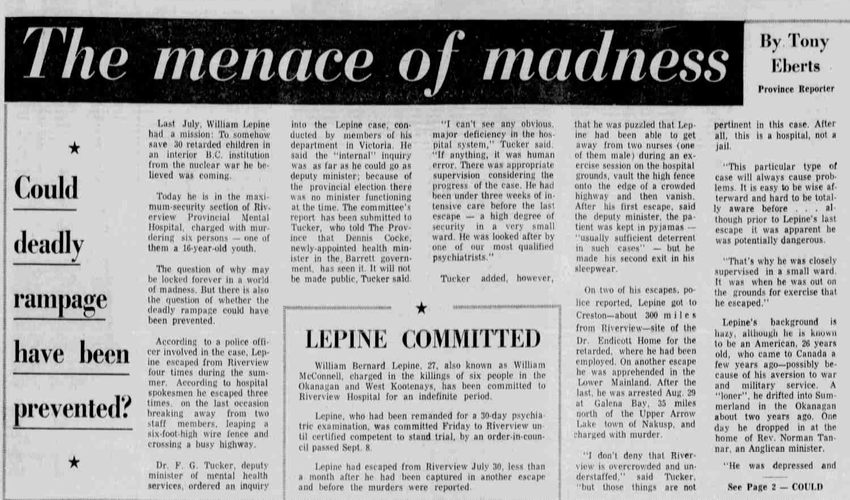

Lepine was hospitalized at the Riverview Hospital in Coquitlam, but managed to escape at least twice.

Two months before the killings, Lepine escaped and was captured following a 30-kilometre, high-speed car chase, which ended with his vehicle flipping over on Highway 3.

A 1972 Province article went with the headline The menace of madness – Could deadly rampage have been prevented?

“A wave of sorrow, shock and fear is following in the wake of this senseless series of killings. It is particularly evident in the interior communities most closely involved in the deaths,” the Province reported. “Demands are being made for more adequate protection of the public from mental patients who may be dangerous. There should be more intense and prolonged care for psychotics who show violent tendencies say community spokesmen; institutional security should be tightened to reduce escapes.”

The 53-year-old article says such demands aren’t new and the institution has been “overcrowded and understaffed for many years.”

Bathgate was only 17 years old when he caught a lift that day and says he doesn’t really remember being too scared.

“I was just a young hippie doing my own thing, I was very independent even at that age,” he said.

A few years ago Bathgate published a book of short stories, All Roads at Any Time, about his adventures hitchhiking across Canada as a teenager.

The 1970s were a heyday for hitchhiking, and the night of killings, he made it to Kelowna and the next day was back in Victoria at his parents. He didn’t call to say he was OK.

“I knew I was going to see them the next day right so I didn’t even I didn’t even check in,” the 70-year-old said.

Bathgate doesn’t think he was really ever that close to Lepine on the day, but the episode has always remained in his mind, especially after a chance encounter 30 years ago.

He’s not sure how it came up, but he realized he was working with one of the grandchildren of Allan and Mildred Wilson, who had been shot and wounded at the campsite.

He became friends with both grandchildren and several years ago attended by phone Lepine’s BC Review Board hearing.

“It was just an old guy talking about… how he’s really turned a corner and he’s a good guy now but… then he revealed within that conversation that he still thought he did a good thing by doing what he did,” Bathgate said. “I thought maybe this would be something revelatory but in fact it was an old tired man in a prison who’s been incarcerated for 50-plus years.”

The recent Review Board decision says Lepine has been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

“However, he has continued to verbally threaten staff and has demonstrated that he is capable of violent behaviour towards co-patients,” the decision reads.

In 2024, he was charged with assault after he punched another patient in the head 10 times. Crown prosecutors later stayed the charges.

“His mental condition will likely decline with the advancement of his Parkinson’s disease, and he remains capable of inflicting physical and psychological harm on others. The Board has no doubt that he remains a threat to the safety of the public,” the decision reads.

The Review Board ruled Lepine can have escorted access to the community, provided he is with two staff members whom he knows well and is in an open area away from the public.

News from © iNFOnews.ca, . All rights reserved.

This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.