Cuomo hasn’t condemned bigoted attacks on Mamdani. In 1977 race, his father took another approach

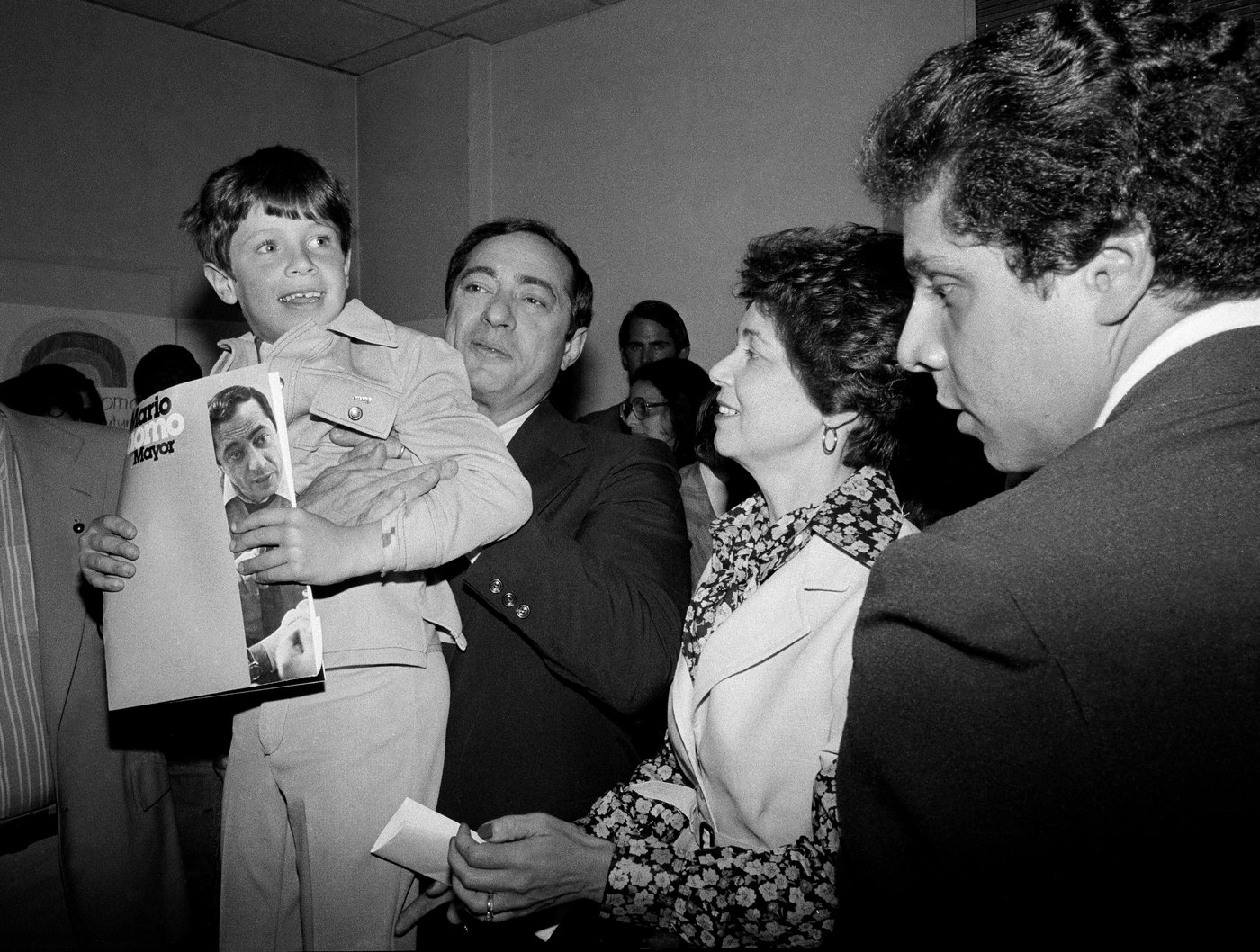

NEW YORK (AP) — In 1977, at the tail end of another bruising battle for New York City mayor, Mario Cuomo publicly spoke up against bigoted remarks leveled at his opponent. Almost 50 years later, his son is taking a different approach.

Back then, Andrew Cuomo was a 19-year-old adviser to his father, who would later become the state’s governor but at the time was losing the mayor’s race against the Democratic nominee, Ed Koch.

A few weeks before the election, posters appeared in some neighborhoods referencing Koch’s long-rumored sexuality with the slogan: “Vote for Cuomo, Not the Homo.”

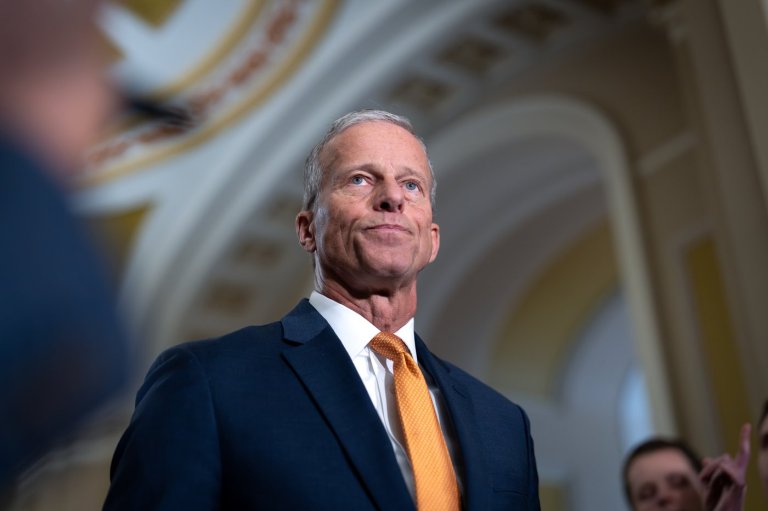

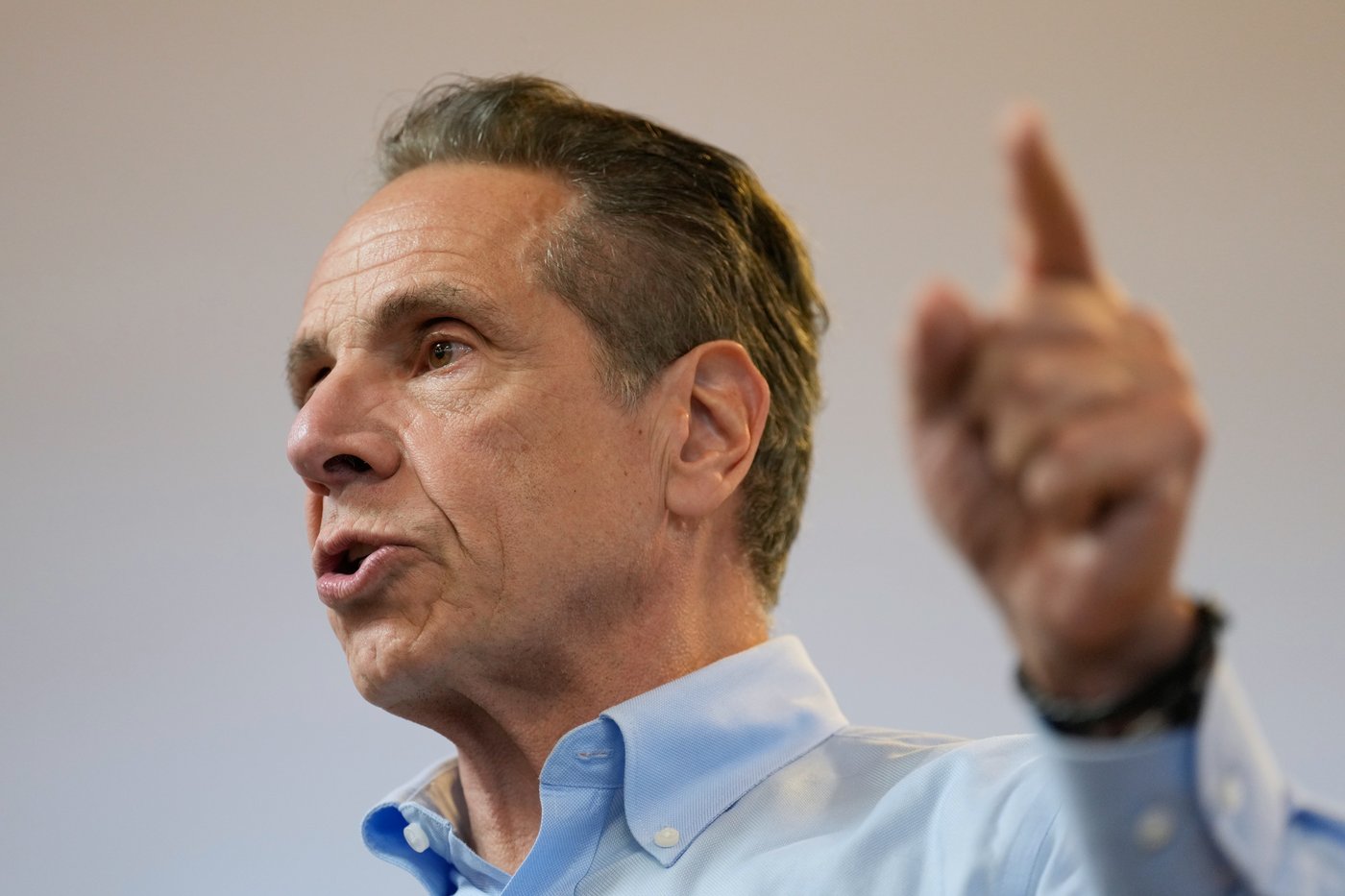

This time around, it’s Andrew Cuomo’s backers disparaging Democratic nominee Zohran Mamdani, who would be the city’s first Muslim mayor, as an Islamic extremist.

But Cuomo has done little to discourage them, drawing allegations that his campaign is embracing Islamophobia, or is at least willing to capitalize on it.

Cuomo, in a recent phone interview, said he isn’t responsible for the words of others.

“What is the standard now?” he said. “You have to respond to everything that is said?”

That approach stands in sharp contrast to that of his late father, who publicly warned against insinuations about Koch’s sexuality, calling the tactic “stupid” and “childish.”

“What if you hurt this fellow and he wins — which he might,” Mario Cuomo said in an interview published days before Koch’s victory. “What you’ve done is you’ve scarred the reputation of the mayor of the greatest city in the world.”

Daniel Soyer, a history professor at Fordham University focused on New York politics, said the disparate reactions point to a “coarsening of the political discourse in general.”

He noted the focus on Koch’s sexuality came as gay New Yorkers were first gaining political power, mirroring the recent growth of Muslim voters as an electoral force.

“In both cases,” Soyer said, “the emergence of these constituencies brought backlash from people trying to paint them as illegitimate participants in mainstream politics.”

Cuomo says he is not the divisive one

Asked about the comparison, Cuomo argued that it was Mamdani, not him, who had leveraged criticism of Israel as a wedge issue in the campaign.

“My father was saying don’t raise gay as an issue. There’s no place, don’t divide people, don’t play that kind of politics,” he said. “And to me that is a mirror to what Zohran’s doing, exactly.”

“You don’t want to create wedges and division,” Cuomo continued. “And there is no one associated with me, standing next to me who’s ever done anything like that.”

Many in his own party — including some centrist Democrats — disagree, pointing to a barrage of attacks both online and in person that Cuomo has largely avoided denouncing.

Appearing on a conservative radio show last week, Cuomo chuckled at host Sid Rosenberg’s suggestion that Mamdani would be “cheering” on another 9/11 attack. “That’s another problem,” Cuomo replied.

At an endorsement event, he nodded along as Mayor Eric Adams implied that a Mamdani victory could make Islamic terrorism more likely in the city.

A new ad funded by a Cuomo-supporting super PAC places the words “Jihad On NYC” over Mamdani’s smiling face — a reference to a headline about a controversial religious leader who has appeared in photos beside Mamdani and other politicians, including Adams.

Cuomo’s official campaign account, meanwhile, recently shared — and then deleted — an AI-generated video depicting Mamdani eating rice with his hands, something critics have used to mock his South Asian heritage. A spokesperson for Cuomo said the video was posted in error.

Mamdani sees the attacks as part of a familiar playbook.

“To be Muslim in New York is to expect indignity,” he said Friday. “But indignity does not make us distinct. There are many New Yorkers who face it. It is the tolerance of that indignity that does.”

In response, Cuomo said his opponent’s views toward Israel, including allegations that it committed genocide in Gaza, had “created real fear in Jewish communities.” He acknowledged that Rosenberg’s comment was “offensive,” but maintained that “nobody is attacking (Mamdani) for being Muslim.”

His own staunch support for Israel, Cuomo said, might be compared to his father’s vocal opposition to the death penalty — another issue outside of a mayor’s control, but which nonetheless animated the 1977 race amid growing fears of crime and disorder.

“Eighty percent of New Yorkers supported the death penalty and he wouldn’t change his position,” Cuomo noted. “I’ve supported Israel all my life. I get the political consequence.”

‘If Mario Cuomo were here today…’

To this day, the exact origin of the posters remains a matter of dispute. Koch would go to his grave blaming Mario and Andrew Cuomo, though both have denied involvement.

“Nobody ever accused my father’s associates of having anything to do with that,” Cuomo said by phone recently.

Shortly before the election, Mario Cuomo’s campaign manager admitted to a Village Voice reporter that he had investigated rumors of Koch’s homosexuality. Mario Cuomo received the news with horror. “Oh Christ,” he told the reporter. “Holy mother of god. I’m so…I’m so…disappointed.”

The outrage over the signs extended to some of Koch’s opponents, recalled Allen Roskoff, who chaired Lesbians and Gays for Mario Cuomo in the 1977 race, noting that his boss may have been “motivated by political expediency as much as his own conviction.”

“The big difference now is that there doesn’t seem to be anyone in the pro-Cuomo camp that is taking umbrage to this anti-Muslim demagoguery, which is effectively condoning it,” said Roskoff, who now chairs the influential Jim Owles Liberal Democratic Club and plans to vote for Mamdani.

“If Mario Cuomo were here today,” Roskoff added, “he would be holding a press conference saying this is wrong and it’s not what a campaign should be about.”

Join the Conversation!

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.