Elevate your local knowledge

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Selecting your primary region ensures you get the stories that matter to you first.

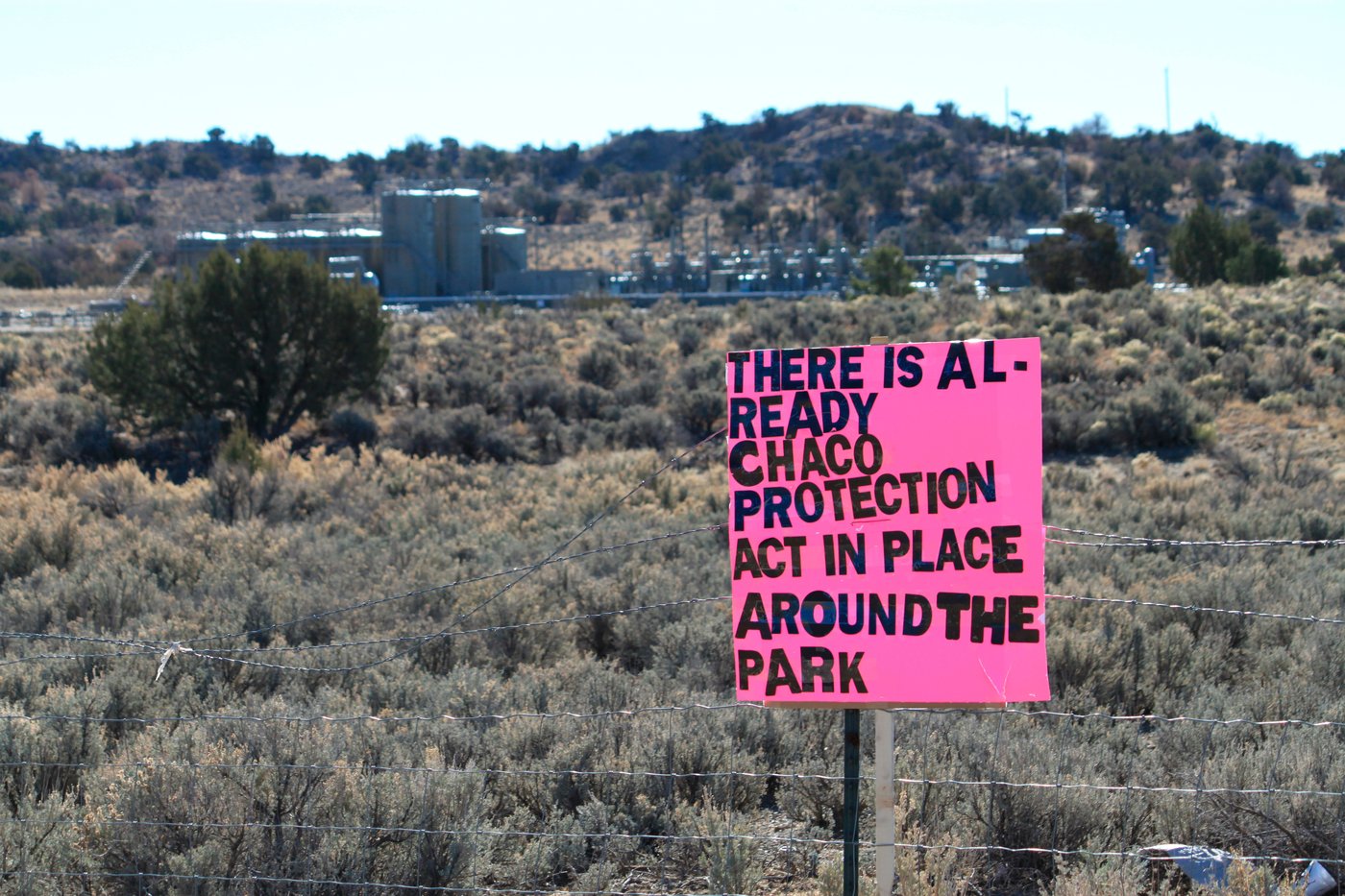

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. (AP) — The Trump administration says it will be initiating formal meetings with Native American tribes in the southwestern U.S. as it considers revoking a 20-year ban on oil and gas development across of hundreds of square miles of federal land surrounding Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

The Bureau of Land Management made the announcement in a letter sent to tribal leaders last Thursday, saying the agency will conduct an environmental assessment of the proposal to put the federal parcels back on the board for future leasing. A public comment period will follow.

The UNESCO World Heritage site has been at the center of a fight over drilling for years, having spanned multiple presidential administrations. Within park boundaries are the towering remains of stone structures built centuries ago by the region’s first inhabitants, and ancient roads and related sites are scattered farther out across the desert plains and sandstone canyons.

With the urging of some pueblo leaders, former President Joe Biden’s administration in 2023 issued an order banning new oil and gas development for two decades within 10 miles (16 kilometers) of the historic site in northwestern New Mexico.

Tribal leaders who had celebrated the move and New Mexico’s Democratic congressional delegation are now concerned the protections could be rolled back as President Donald Trump’s administration reconsiders a host of public land orders issued under Biden.

The Interior Department did not immediately respond Monday to an email asking about the latest correspondence with tribal leaders on the Chaco proposal, but said previously that it takes its tribal trust responsibilities seriously and will continue to engage in government-to-government consultation.

The letter indicates BLM will consider three options: leave the withdrawal in place, revoke it in full or opt for a smaller buffer around the park.

It also notes that the process is a priority for the department and that despite the government shutdown, BLM staff would be available to talk with tribal leaders at their request.

Pueblo leaders traveled to Washington, D.C., in September to advocate for the withdrawal to be kept in place and for legislation that would make the ban permanent.

“Our bloodlines, our heritage, our cultural foundation, our identity comes from Chaco Canyon,” Santo Domingo Pueblo Lt. Gov. Raymond Aguilar said during a news conference not far from the steps of the Capitol. He likened Chaco to D.C., an important place where leaders serve a mission to protect their people. He said pueblo ancestors who called Chaco home were stewards of the land and that it still serves as a center of prayer today.

From Acoma and Laguna pueblos in New Mexico to the Hopi people in Arizona, oral histories and cultural traditions link back to the Chaco region. At Picuris Pueblo, researchers also have used DNA to link tribal members to the ancestral site — something pueblo members hope will give them a greater voice in shaping decisions about the future of the area as development pressures loom.

The debate over the buffer around Chaco has pitted the Navajo Nation against other tribes in the region. Some Navajos have called for a smaller area to be protected as a way to preserve the oil and gas royalties and other revenues that some families depend on.

In January, the Navajo Nation sued, alleging that the U.S. Interior Department under Biden did not properly consult with its members about the economic impacts on tribal communities of prohibiting new oil and gas leasing and mining claims. The complaint doesn’t seek revocation of the withdrawal, but rather challenges the process through which it was implemented.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.