Elevate your local knowledge

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Saving a life is more important than policing small amounts of drug use, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled last month.

The ruling clarified the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act, which was passed in 2017 and offers legal protections for people who call 911 in response to an overdose.

The act encourages people to call 911 if they witness an overdose.

The recent ruling clarified that people who make a potentially life-saving call — along with the people who are overdosing and others at the scene — are protected from being arrested or charged for drug possession, even if police show up and see drugs.

Simple drug possession generally means having a small amount of drugs for personal use.

Corey Ranger, president of the Harm Reduction Nurses Association, said it’s incredibly important to immediately call 911 and stay with the person who is overdosing. The Harm Reduction Nurses Association, the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition and the Association des intervenants en dépendance du Québec intervened as a coalition in the Supreme Court case, arguing that the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act has to be easy to trust and understand for it to work as a harm reduction tool.

Delaying emergency care by not immediately calling 911 can result in brain injury, trauma and preventable death, Ranger told The Tyee. Staying on the scene to help the overdosing person can also mean the difference between life and death, he said.

What to do if someone overdoses

If you witness someone overdosing or find someone unresponsive, call 911 right away, Ranger said.

The 911 operators can guide a person through how to give emergency breaths and other basic first aid.

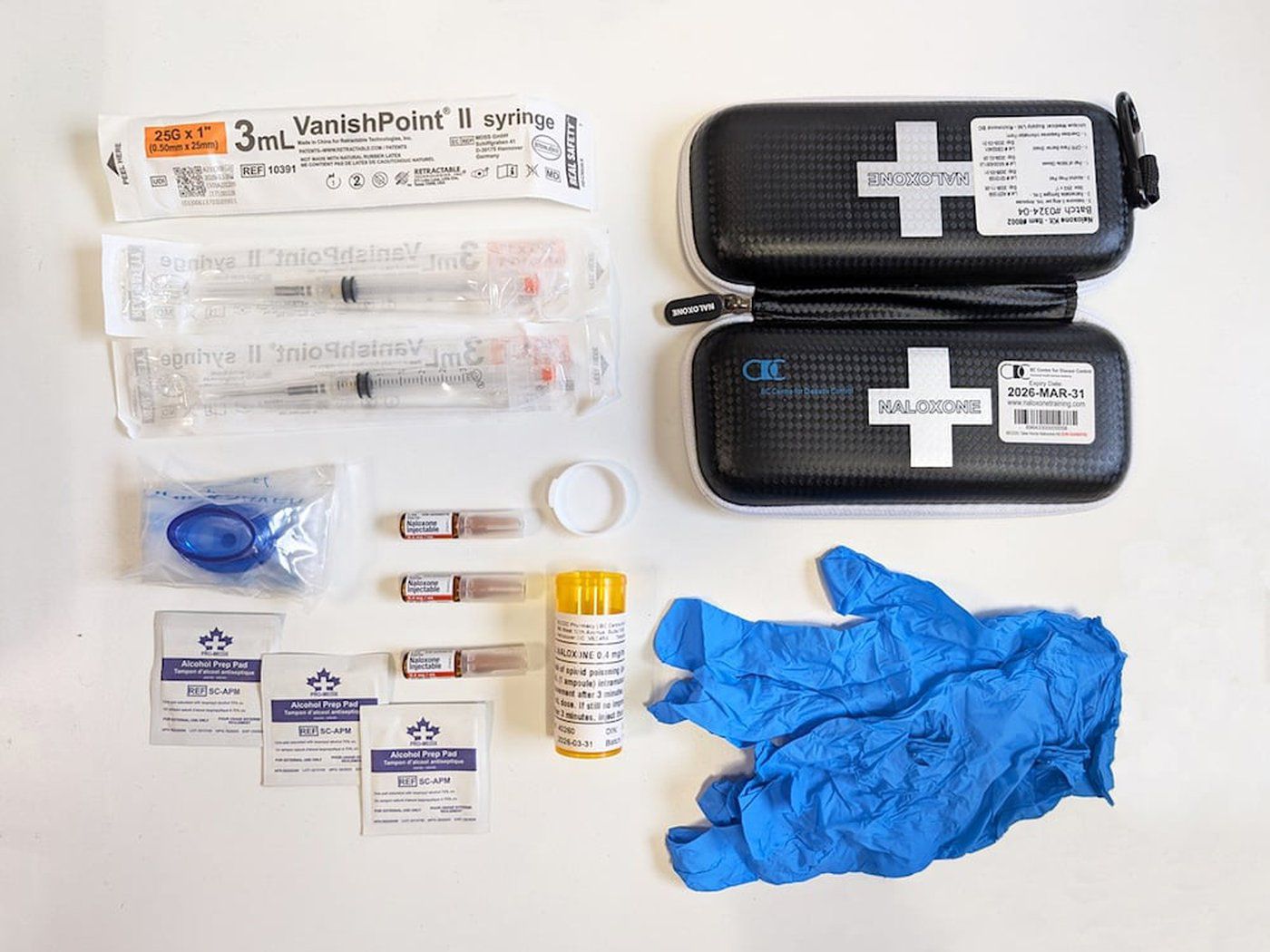

Administer naloxone if you have it. 911 operators can also walk a person through naloxone administration.

Stay with the person until emergency crews show up.

Free online naloxone training from Toward the Heart’s website says it’s important to still call 911 even if you carry naloxone because first responders can check for other reasons a person could be unconscious or not breathing, such as spinal injury, an allergic reaction, low blood sugar or a seizure.

Illicit drugs also increasingly contain dangerous levels of other substances that are not affected by naloxone, such as benzodiazepines, which can further depress breathing; xylazine, which works as a tranquillizer; and stimulants, like cocaine and methamphetamine. Alcohol can also increase the risk of overdose and death.

Naloxone temporarily blocks opioid receptors, which reverses an opioid overdose. Opioids can last in the body longer than naloxone, so it is possible a person will overdose again when the naloxone wears off.

Naloxone is not harmful and has no effects other than blocking opioids, so there’s low risk to administering it to see if it helps.

People can get naloxone or training on how to administer it for free from almost any pharmacy in B.C., or any other location listed on Toward the Heart’s website.

“It’s not just about reducing death; it’s about reducing irreparable harms,” Ranger said, referring to timely emergency responses to overdose.

What the Supreme Court clarified

When the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act was introduced, it protected people from being charged or convicted for simple drug possession if they called 911.

But in Saskatchewan in 2020, Paul Wilson called 911 to report a companion had overdosed. He stayed with her to administer emergency first aid and likely saved her life. When police arrived, they arrested the woman, Wilson and others for simple drug possession, according to the Supreme Court case.

The police used the arrest as grounds to search Wilson’s vehicle and eventually charged him with trafficking and other offences based on what they found in the search.

Wilson challenged this in court.

The case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court of Canada, which ruled that police never should have arrested Wilson in the first place.

“The court has been clear: you cannot be arrested for simple possession at the scene of an overdose. So call 911,” said DJ Larkin, executive director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition.

Police discretion

Larkin said it isn’t clear how the Good Samaritan act has changed police practices.

“We don’t collect national data on arrests for simple possession,” Larkin said.

Sarah Blyth, executive director of the Overdose Prevention Society, said she hasn’t met anyone in Vancouver who is afraid of calling 911 during an overdose and has never heard of anyone being arrested after calling for help.

However, she said she could understand if young people who weren’t very experienced were afraid to call 911 and hopes they’ll now know to call.

“In the moment, you don’t want to be thinking about other things when you’re trying to save a life,” she said.

The Vancouver Police Department’s 2025 regulations and procedures manual says officers should attend an overdose only if there is a fatality or threat of violence.

That’s been the strategy since 2006, when the agency recognized sending police to respond to overdose calls could deter people from calling for help during an emergency, VPD spokesperson Sgt. Steve Addison told The Tyee in an email.

However, Police Oversight with Evidence and Research, or POWER, has reported how some officers in the Downtown Eastside have gotten in the way of harm reduction workers administering naloxone or first aid.

POWER is a research project founded in 2024 by the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users and the Western Aboriginal Harm Reduction Society.

Academic studies have also found knowledge of the Good Samaritan act varies widely among police officers, simple possession is still used by police as an enforcement tool, and police are confiscating drugs without arresting people.

Confiscating drugs causes harm

Larkin said there’s a lot of grey area between what police decide is simple possession versus trafficking.

What a person might use in a single day will also vary, Larkin said, adding people with strong habits might buy in bulk or package their drugs in smaller portions to reduce the risk of having all of their drugs confiscated or stolen.

The Supreme Court ruling says, “Parliament prioritized saving life over the more remote public safety benefits of arresting persons at the scene for simple possession.”

Larkin said this opens the door to an important larger discussion where the courts can question if, and how, arresting people for simple possession improves public safety.

While police often say arrests and drug confiscations help, Larkin said, “there’s almost no evidence for this and academic studies also don’t support it.”

“Drug confiscation doesn’t make drugs less available or stop people from using; it just makes it more dangerous,” Larkin added. Seizing someone’s drugs has been found to increase their risk of an overdose, increase drug deaths and increase community-level violence, Larkin said.

If police do show up at an overdose call, Larkin recommended that people put drugs away in their pockets or out of sight, keep their hands where police can see them and, if asked to consent to a search, ask if they’re being arrested and, if so, why they’re being arrested at an overdose call.

— This article was originally published by The Tyee

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.