Elevate your local knowledge

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Selecting your primary region ensures you get the stories that matter to you first.

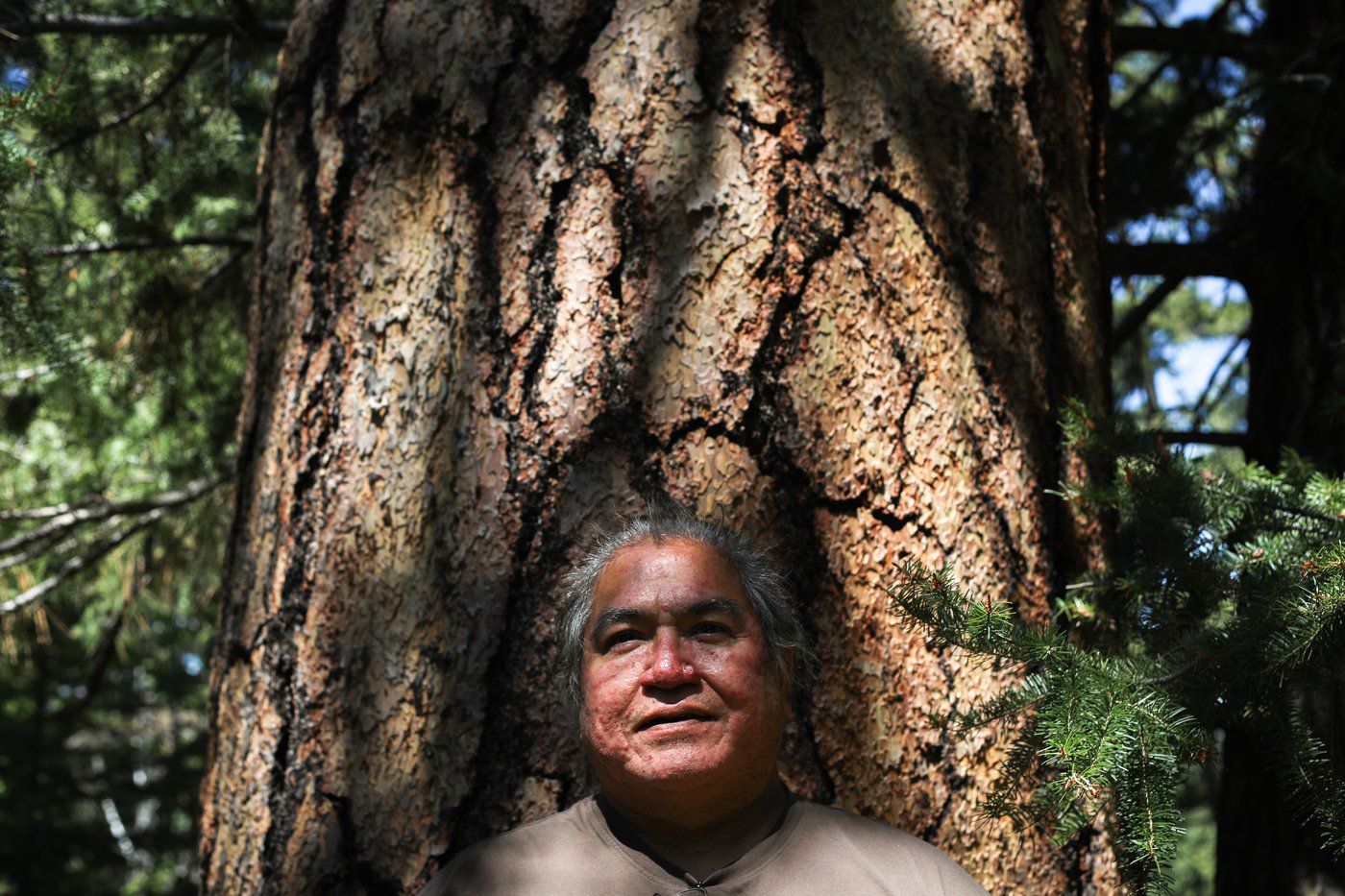

Growing up in Nlakaʼpamux and syilx territories in the 1970s, Joe Gilchrist can’t remember a single summer when wildfire smoke ever trapped him indoors.

The Merritt, B.C., region’s semi-arid landscape still saw scorching summer temperatures back then, he recalled, but not the record-breaking fire seasons of recent years.

“That was thanks to our work that the Indigenous ancestors did on the land,” said Gilchrist, a Secwépemc Nation member who now lives on Skeetchsn Indian Band’s reserve with his daughter.

“Then, everything was still fairly spaced out; the fires were easier to handle.”

Although settlers’ wildfire suppression efforts had become the dominant form of land stewardship when he was young, Indigenous communities in the Nicola Valley were still using fire to “cleanse” the land, Gilchrist said.

Cultural burning was a key part of Indigenous land stewardship for “thousands of years,” he told IndigiNews. “It was all across Canada — it used to be done to the north, the south, the east and west.”

Taking his advocacy to UN climate talks in Brazil

Now in his 50s, Gilchrist today is playing a leading role in uplifting and advancing his ancestors’ fire keeping traditions — and sharing that wisdom far beyond his own nation’s territories.

But he didn’t always conduct burns. For three decades, Gilchrist served as a professional firefighter.

Since retiring from that career, he has assumed the role of a traditional Indigenous firekeeper.

That work now takes him around the world to promote the benefits of Indigenous land stewardship — in particular how to cleanse the landscape with cultural burning — in hopes of making it more widespread internationally.

This month, his mission took him far south to Brazil — where he spoke at the United Nations climate summit, COP30.

At that major international event, he shared his extensive experience as a leader in a growing Indigenous-led fire movement. The summit saw fierce confrontations between security and Indigenous land defenders.

“I got into talking, presenting and just seeing the importance and the need for cultural burning as climate change happened,” he said in an interview before his departure.

“Seeing that the forest was too thick — that it needed to be looked after properly.”

He’s also been to Australia, Fiji, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Colombia and UN meetings in Rome to promote cultural burning and land stewardship.

In his travels, he’s met countless fellow Indigenous peoples who share and advocate for those same values — many of them with ancient cultural burning traditions of their own.

Gilchrist is widely recognized for his leadership in the movement in his homelands, serving as vice-chair of the Thunderbird Collective, an Indigenous organization pushing for more cultural fire practices; he’s also a member of the Salish Fire Keepers Society.

Through the Thunderbird Collective, he hopes to train and support Indigenous communities in fire stewardship and cultural burning.

Being a cultural firekeeper requires significant responsibility and time. But he realized advocacy work was also needed — something he’s taken upon himself, after recognizing how frequent and devastating wildfires have become in the era of climate change.

“The loss to fires is getting pretty catastrophic,” he said. “It’s always sad to see the loss.

“There is a better way of looking after the land, so that it’s not so dangerous to the public … It is doable.”

‘Our ancestors used to do that all across North America’

Gilchrist began working with fire when he was just 15, to help support his family, after his carpenter stepdad got injured on the job.

He started his 30-year firefighting career with the BC Wildfire Service in 1982, working with the agency until 2012. He retired from fighting fires shortly after.

In 1991, he was a member of the Merritt Firedevils, a type one all-Indigenous emergency unit crew, which are a group of firefighters who are “usually the first to arrive at a fire site to suppress a wildfire,” the BC Wildfire Service states.

One year later, he became the crew’s leader, through which he travelled all over the country to fight fires.

Not only did Gilchrist help battle wildfires. He also carried on the prescribed burning traditions of his ancestors during this time, too.

In 1996, he moved to full-time work with the BC Wildfire Service, completing a 16-week government training program, Indigenous Fire Prevention.

That’s where he began to learn more about fire prevention and Indigenous use of fire to steward the land.

He also discovered the practice wasn’t just common in his own territories.

“It’s amazing that our ancestors used to do that all across North America,” he said. “It goes all the way down to South America, Africa, Australia — the whole thing was all burning.”

Fires increase nutrients, medicines and food security

Historically in his region, Gilchrist said Indigenous people conducted low-intensity controlled burns every spring and fall to support different habitats and maintain varying landscapes — including deterring forest over-growth.

The ancestral practice — also known as prescribed or cultural burns — helped “cleanse the land” by preventing trees from encroaching on one another. This kept forests healthy by decreasing fuel — such as low-hanging branches, small or dead trees, and other vegetation —from accumulating as time passed.

“When you burn it lightly in the springtime, the fire consumes the fuels and turns it into nutrients for the plants,” Gilchrist explained.

But, he emphasized, that process was never a one-off. Treating forests with light burns needs to happen every seven to 15 years.

“You can’t just do work on the forest just once,” he said. “It has to be continuous — it has to be more of a lifestyle change.”

During prescribed burns, trees are pruned by slashing low-hanging branches. This tactic thinned forests and created more space between trees. It also helps prevent fires from climbing to treetops and spreading to others.

Slashed branches are piled with the other gathered fuel and sometimes burned at a later date, which was typically sometime in the winter season.

“The longer that you don’t have fire on the ground, the fuel builds up,” Gilchrist said. “But also the forest encroaches on itself — trees become denser and thicker.

“Then they become diseased, because there’s only so much water for the trees and for the land.”

Different burn cycles achieved different landscapes, and helped prevent trees from taking over, he said.

“That’s how it was for thousands of years,” he said. “And if you don’t do that, you get to where we’re at now, where it’s too thick.

“It happens if you don’t look after the land — if you don’t steward the land with fire.”

Historically much of the Nicola Valley was grassland, rather than the thick forests found in many areas there today, he said.

Since ancient times, the local valley bottoms were host to massive cottonwood trees, growing alongside Indigenous pithouses and other traditional structures.

Firekeepers maintained those grasslands and meadows by burning the land every two years, he said. Controlled burns destroyed any tree seedlings, needles or pine cones, preventing them from spreading.

But thinning the woodlands also made hunting easier, too.

The practice helped local communities, too, improving hunting areas and encouraging different medicines to grow in the open grasslands left by burning.

“You have to burn every two years — perpetually — for thousands of years, and it’ll stay a healthy grassland,” he said.

“But once you miss a few burn cycles, the trees become taller than the light burning can kill. Eventually, the trees start to take over.”

In the fall, at higher elevations, burning every four years allowed huckleberry patches to grow and prosper. These burns also nurtured other medicines, and habitat for both ungulates and wetland species.

Light burns along river banks helped deepen and strengthen the roots of some deciduous trees — such as cottonwood, willow and alder.

Encouraging those trees to flourish helped keep the water cool for fish, as it provided patches of shade over a waterway. It also protects river banks from erosion and flooding.

“There’s a lot of reasons and ways that the fire was used in a good way,” he said.

A large Indigenous settlement once stood where the City of Merritt is today, at the junction of the Nicola and Coldwater rivers.

“The area around the community was burned just for protection and safety from fire in the summer time,” he recounted.

“Everything was known, especially by the matriarchs of the land … The females kept the stories of when it was last burned, where the medicine is picked, where the berries were ready, when it needs to burned again.”

To settlers, ‘fires must’ve looked dangerous, I guess’

Settlers built their houses and towns out of wood, often in the middle of heavily forested, fire-prone areas.

“A lot of people want to live in the forest with the trees,” Gilchrist said. “They don’t want to see fire in the trees.”

This practice of low-intensity controlled burns slowly became less common by the end of the 20th century, as settlers’ worldviews about land stewardship and suppressing fire came to dominate.

“I think it was the fear of fire,” Gilchrist mused. “Seeing people lighting fires must’ve looked dangerous, I guess.

“You make that illegal — so that people aren’t adding fire to the land — then you just start putting out fires that you see.”

Summertime wildfires, many sparked by lightning, began to threaten colonial settlements — and this is when Gilchrist believes today’s rapid-response fire-suppression model took root. It was a “hit fast, hit hard” approach of wildfires, he said.

In a semi-arid landscape — unless there are smaller, frequent burns to consume fuels that fall to the ground —that natural debris will pile up and dry out even more.

”They don’t deteriorate,” he said. “They just stay on the ground and wait for fire — it just keeps building up and building up.

“It just becomes more and more of a danger, the longer that you don’t have a fire on the land … Now we’re seeing huge megafires because of that kind of land stewardship.”

Gilchrist sees cultural burning as a type of medicine for the ecosystem. Suppressing that medicine, in favour of reactionary firefighting efforts, have now resulted in the fuel-filled forests that we have today — as he sees it, thick and sick with disease and debris.

“Now, we’re seeing responses becoming ineffective, because the fires are just too intense,” he lamented. “With climate change, the only thing you can really change is the fuel.

“Over thousands of years, it was done. It’s a cleansing. It was made natural by Indigenous people.”

Today, combined with the effects of climate change — hotter, drier and even windier summer conditions — has created “the recipe of megafires,” he said.

“The earth can only handle so much trees on it, because there’s just not enough rain, not enough moisture, to support the amount of trees that are here,” he said.

As the climate has changed, so has the typical fire season. At one time, Gilchrist recalled, that season would usually be over by early September.

“Now, we’re seeing it move into October, maybe even longer,” he said. “The burn seasons are even getting longer, too, with climate change.

“That’s just adding more and more of a danger to society.”

Learning to apply fire ‘when we could, as often as possible’

During his decades-long career with BC Wildfire Service, Gilchrist helped conduct hundreds of prescribed burns “for all different reasons.”

In that time, him and his crews applied fire across thousands of hectares around Merritt and the surrounding Nicola Valley, even going as far as Lytton and Hedley.

That work often involved partnering with municipalities and First Nations.

And like how his own ancestors conducted that work, different burns were done in the spring and fall seasons.

“We did elk, deer and moose habitat burns, even mountain beaver,” he recalled. “As we discovered person-caused fires, we would burn those, too.

“We applied fire just when we could, as often as possible.”

His crew favoured a “light hands on the land” approach to their prescribed burn work, when possible avoiding heavy fire-suppression machinery such as bulldozers.

Areas that required prescribed burns were determined by their proximity to a community — such as creating a 2.5-kilometre “buffer” around the City of Merritt, he said.

Previous prescribed burn work he and his crew didultimately helped mitigate the Lily Lake wildfire outside of Merritt in 1999, which burned approximately 110 hectares.

“We burned it at nighttime to control it,” he recalled. “We did a lot of work around that area.”

Revisiting burns of the past

In July, Gilchrist brought IndigiNews to visit places he’d applied fire to decades ago, such as a forested area around Fox Farm Road. He estimates it’s been at least 20 years since the area was treated.

At the city’s north end, Gilchrist showed IndigiNews another area he once treated with fire, roughly 15 years ago.

He pointed out how signs of his work can still be seen today, for instance how well-spaced the trees are from each other, he noted, and how their lower branches had been pruned to reduce wildfire fuel.

But in the years that passed, piles of needle droppings from the tree branches had since accumulated into a thick layer blanketing the ground.

“You can pick it up and hear it crunch,” he said. “It’s not powdery yet, but it’s still able to burn.”

Over the course of 20 years, he also did fire mitigation work on the property around his sister’s home in Nooatich Indian Band, within Nlaka’pamux Nation.

That work included cycles of spacing and removing damaged trees, slashing, piling, and burning every two to five years.

The results of his work there, he said, offer proof of the importance of ancient fire practices amidst climate change.

When the catastrophic Lytton fire jumped the Nicola River and swept through the area in 2021, his sister’s home remained unscathed, even though it was made of logs.

But it also underscored how personal the climate crisis has become for many. Just months later, that fall’s catastrophic atmospheric river flooded the region, and “washed away” his sister’s log house, Gilchrist said.

A high-stakes future for future generations

Nearly 50 years since his youthful days in Merritt, smoky summers — for weeks or even months — are no longer a rarity for communities in the province’s Interior.

Nowadays, such summers have simply become normal and expected, along with their air quality warnings and extreme health concerns that come with them.

“Our kids are going through that,” Gilchrist lamented.

In syilx Okanagan homelands, for example, smoky summers have seemingly been normalized in recent years — with local media outlets even using terms like “Smoke-anagan” to describe the distressing climate-fuelled trend.

Since 2021, there have been more than 1,600 wildfires each year in B.C., according to the province. Two years ago, nearly 2,300 fires burned 2.8 million hectares — 300,000 more hectares than the record-breaking 2017 and 2018 wildfire fire seasons combined.

Niigaan Sinclair, an Indigenous scholar and commentator, told the National Observer that one in seven First Nations in Canada experienced being evacuated during this year’s wildfire season.

Gilchrist himself said that he’s been evacuated at least five times in the last five years.

He noticed that wildfire seasons were starting to worsen following the 1994 wildfire in snpink’tn (Penticton), also known as the Garnet fire, which saw 5,500 hectares burned; over 3,500 people evacuated and 18 homes and structures were lost.

Amidst the climate crisis, Gilchrist says the devastation wrought to worsening wildfires could be likened to a form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“There’s kind of like a PTSD that people get when they see fire and things like that,” he said.

“When you wake up in the morning and the valley is filled with smoke — you wonder where the fire is at, whether it’s going to be a danger to yourself.”

48 prescribed burns in B.C. last year — half involving First Nations

Gilchrist said that prescribed burn work in the province is “slowly” going in the right direction, “but it needs to be multiplied hundreds of times.”

Last year, 3,400 hectares of land were treated with 48 cultural and prescribed burns — 23 of them in partnership with First Nations, according to the B.C. Wildfire Service.

That’s more than double the total number carried out the year before, and up more than a third from 2022.

The planned burns are skyrocketing year-over-year. This year saw 135 planned, the provincial fire agency said.

But even with the increase in such projects, Gilchrist said even more are needed to keep the land healthy. He believes hundreds of thousands of hectares across the province need to once again be treated with prescribed fire.

“We’re not burning enough,” he said. “It’s just a mind-boggling amount of work that needs to be done … We need to speed things up.”

But even as authorities increasingly support the ancient practice, he believes prescribed and cultural burns need even more buy-in from government, academia and media.

During the Thunderbird Collective’s first formal gathering in snpink’tn (Penticton) in September, the group heard from numerous Indigenous communities about the colonial barriers they said still exist against cultural burning, including regulatory and permitting challenges.

So public education is increasingly essential, Gilchrist said.

“Start spending more on prevention, wildfire mitigation and Indigenous land stewardship,” he said.

More planned fires on the landscape bring not just greater ecological health, he emphasized. They also offer financial savings.

“You’ll start spending less money on suppression. People know that there is a better way of managing the forest and the land,” he said.

“My thing now is pushing for Indigenous land stewardship and the Indigenous use of fire on the land. We need to get things going.”

— This story was originally published by IndigiNews

News from © iNFOnews.ca, . All rights reserved.

This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.