Elevate your local knowledge

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Selecting your primary region ensures you get the stories that matter to you first.

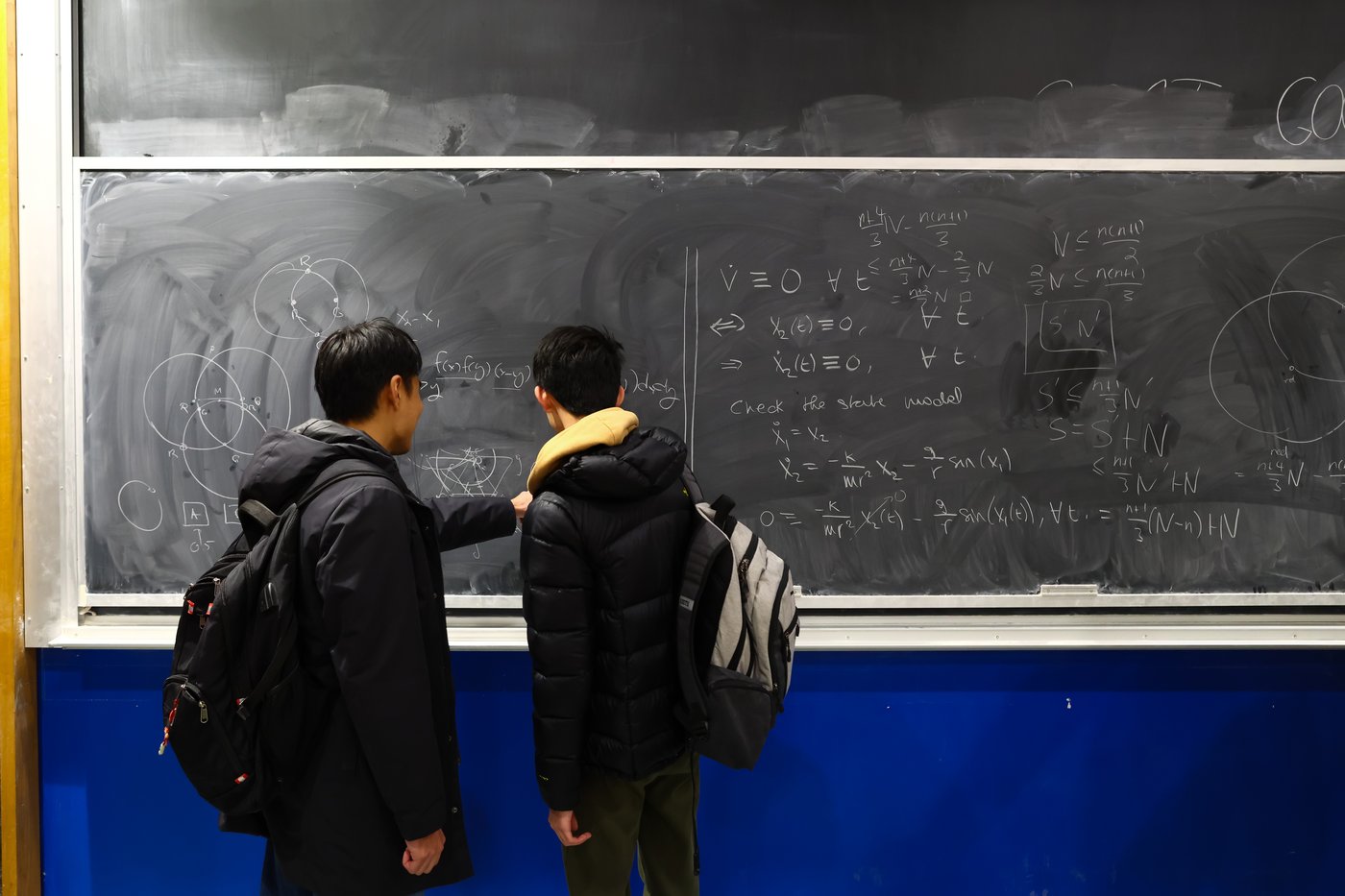

ST. JOHN’S — Undergraduate students across North America sat down on Saturday to write a gruelling six-hour math exam, many of them unlikely to solve a single problem.

The notoriously brutal William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition is more of a mathematical sporting event than an academic test. The annual exam attracts thousands of students, most of whom are unlikely to score more than three points out of possible 120.

Still, fourth-year undergraduate student Gavin Hull was cheerful as he arrived at the empty mathematics building at Memorial University in St. John’s on Saturday morning, ready to tackle 12 mind-bending problems.

“It’s me and the problems and three hours,” Hull said before the first half of the exam. “Just sit there and grind it out and see what you can do.”

Known as “the Putnam,” the annual competition for North American undergraduate students is now in its 86th year and falls on the first Saturday of December.

The exam is special because it tests “an intrinsic mathematical ability and creativity that is not so easy to learn,” said Greta Panova, a professor at the University of Southern California. She was part of the team that helped develop this year’s Putnam problems.

“People want to test their limits,” she said in an interview.

Putnam questions are not the type that come up in regular exams or textbooks. They are more like puzzles than calculations, often requiring students to find different ways to represent things before a solution might unfold.

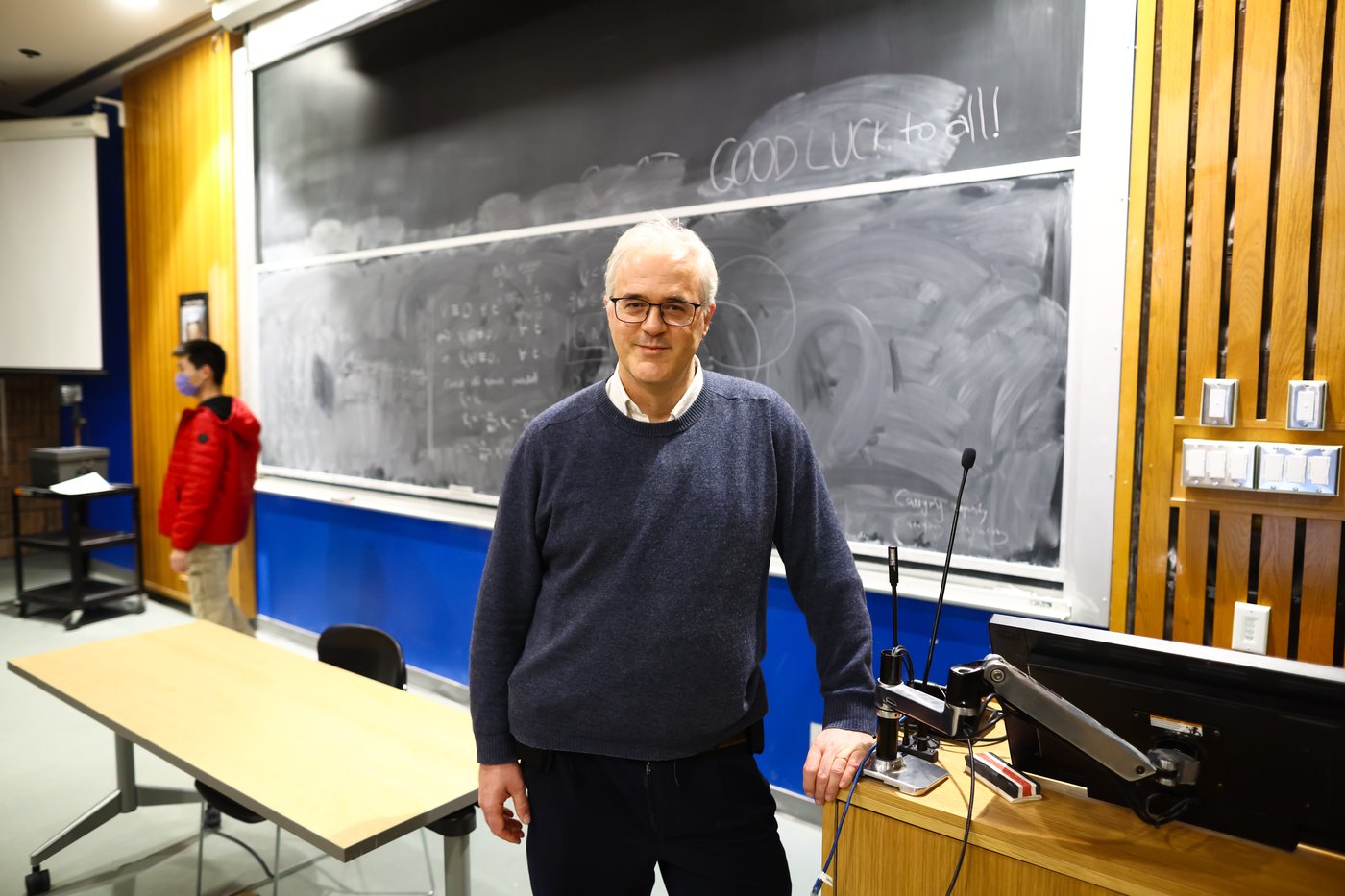

Some competitors at the University of Toronto are driven by a friendly rivalry with the University of Waterloo, which are the schools that tend to produce the Putnam’s highest-ranking Canadians, said Ignacio Uriarte-Tuero.

Uriarte-Tuero is a mathematics professor at the University of Toronto, where he helps students train for the competition through weekly problem-solving sessions.

“I think we will have a good team, but it depends also on the other teams,” he said in an interview. “It’s very similar to a sports competition. You may feel you have amazing athletes. But if the competition has better athletes, then you’re toast.”

There is a “mini rivalry” between McGill University and the Université de Montréal, said Sergey Norin, an associate professor at McGill who helps students prepare for the Putnam.

“One year, when (Université de Montréal) did better than us, they were gloating,” he said, laughing.

In St. John’s, Hull said he practised for “hundreds of hours,” going over past Putnam exams and reading textbooks. He’s written the exam three times before. He was hoping Saturday to beat his past high score of 25 points and finish with one of the top 500 marks.

After the exam, he said he managed to submit solutions for five problems — more than any other year he’d taken part.

Official results are typically released within a few months of the exam.

Last year, nearly 4,000 students across the continent wrote the Putnam. Sixty-one per cent scored three points or fewer, according to the Mathematical Association of America, which organizes the competition. The top score was 90 out of 120. Previous years were not much different.

It’s a tough competition, Hull acknowledged, joking that he felt a kind of trauma bond with the thousands of other students writing it that day.

“But it’s fun,” he said. “I love problem solving. I like puzzles. And this is kind of the ultimate puzzle.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Dec. 7, 2025.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.