Elevate your local knowledge

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Selecting your primary region ensures you get the stories that matter to you first.

Lindsay Gill spent four days in Surrey Memorial Hospital’s emergency department in September.

Gill had been admitted to the hospital soon after arriving, but the Surrey resident had to remain in an emergency department hallway while she waited for a bed to open up in a ward. The energy in the hallway was chaotic, and Gill told The Tyee she felt gratitude and awe for the staff navigating the overcrowded workplace, filled with upset patients.

But emergency departments are not intended for the long-term care of patients, and being stuck in the hallway came with stress. She witnessed, for example, hospital security tackle a man at the foot of her bed.

Stories like Gill’s are far from rare in British Columbia. Over the last decade, the province’s hospitals have consistently operated over capacity. That means people admitted for overnight care are regularly cared for in locations including hallways and emergency room nooks, rather than in spaces designated for ongoing care. It also means nurses and other hospital staff are left caring for more patients than they should be.

Hospital overcrowding leads to more medical errors and less effective care for patients, health-care officials broadly agree. As hospitals approach full capacity, traffic jams emerge and care becomes less efficient. Officials in Fraser Health have been warned that occupancy levels above 95 per cent lead to worse patient outcomes.

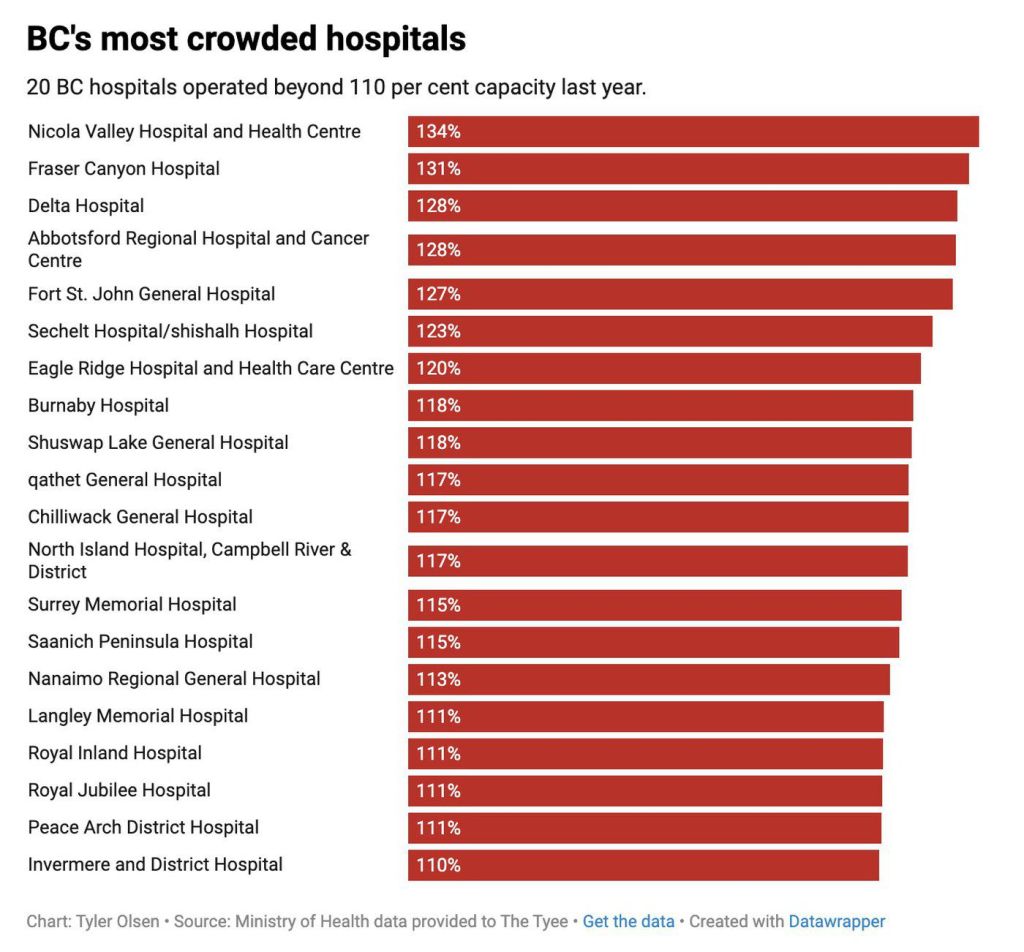

New data provided to The Tyee reveals that seven B.C. hospitals operated at more than 20 per cent over capacity last year. In such hospitals, that means at least one of every six patients is cared for in an “unfunded” bed. Fifty of B.C.’s 87 hospitals had more patients than beds over the last year.

Those hospitals include major facilities in Metro Vancouver, in the Fraser Valley, in the Okanagan and on Vancouver Island, along with smaller sites spread around the province. B.C.’s most crowded hospital in both the 2022-23 and 2024-25 fiscal years was Nicola Valley Hospital and Health Centre in Merritt. Last year, the hospital operated at 133.5 per cent capacity.

The problem, as The Tyee will explore in the second part of this series, is the result of a nexus of complex issues, including a lack of sufficient hospital spaces, ongoing human resource challenges, an aging population and a lack of sufficient places to care for older people who need ongoing care.

The most-crowded hospitals

British Columbia’s hospital congestion troubles go back more than a decade.

Except for the unprecedented year following the arrival of COVID, the province’s hospitals have operated over capacity every year since 2012. (The arrival of COVID at the start of the 2020-21 fiscal year led officials to empty hospitals to prepare for an influx of patients; many long-term care patients also died, reducing the number of elderly patients in hospital waiting for space in a care home.)

Annual hospital performance data paints a grim picture of consistent overcrowding. And the situation is not improving.

When hospitals are overcrowded, patients are placed in so-called “surge beds,” which can be located in hallways, storage areas or other places not designated for full-time, ongoing care. The term “surge beds” has only recently become widely used to describe such spaces. Previously, Fraser Health — the province’s largest health authority — called such spaces “inappropriate locations” in internal memos.

In those memos, officials were told that care in such locations “is not ideal from a patient or staff perspective” and that “maintaining high hospital occupancy (e.g., over 95 per cent) is associated with longer lengths of stay and higher risk for error and adverse events.”

B.C.’s health organizations and their leaders have spoken about their work to reduce hospital congestion for more than a decade, but the figures reveal they have been unable to do so.

Facilities operating above 120 per cent capacity included Fraser Canyon Hospital in Hope, Delta Hospital, Abbotsford Regional Hospital and Cancer Centre, Fort St. John Hospital, Sechelt/shíshálh Hospital and Eagle Ridge Hospital.

All seven have operated over capacity each of the last three years. The list gives a sense of the widespread challenges facing B.C.’s health-care system. Congestion and a lack of capacity plague small hospitals in relatively slow-growing rural communities and facilities serving fast-growing cities.

The poster child for the challenges has often been Abbotsford Regional Hospital, which has 300 beds, a figure that has been repeatedly increased over the past decade. Despite those expansions, however, the hospital operated 28 per cent above capacity last year. That means that, on average, 84 patients spent their night in an unfunded bed.

Abbotsford Regional Hospital is just one of many large hospitals bursting with patients. Many of the province’s biggest facilities operated between 10 and 20 per cent above capacity. Those include Burnaby Hospital, Surrey Memorial Hospital, Langley Memorial Hospital, Chilliwack General Hospital, Nanaimo Regional General Hospital, Royal Jubilee Hospital in Victoria and Royal Inland Hospital in Kamloops. Every day, a combined average of 329 patients in those seven facilities are cared for in makeshift spaces.

The challenges are myriad, according to health experts and the province’s own minister of health.

For a decade, officials have spoken about the need to care for more patients out of hospital. That focus often involves the development of home health programs that deliver care to seniors where they live. The goal is to allow people to remain in their homes as long as possible before needing to move to an assisted or long-term care facility.

In an interview with The Tyee, Health Minister Josie Osborne spoke about the ongoing quest for broader community wellness.

“It’s about modernizing infrastructure and making sure that we’re doing everything possible to reduce those preventable or avoidable hospital visits, to speed up the diagnostics and treatment that people receive, to strengthen care in community so that people stay healthier, they stay independent and they stay at home,” Osborne said.

Patients who arrive in hospital are staying longer

Additional data provided by the Health Ministry points to one reason why progress remains elusive.

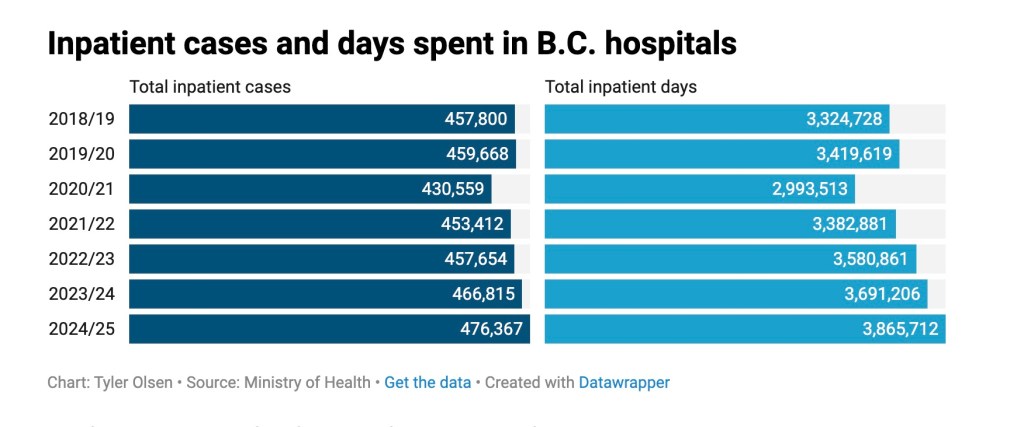

Since 2018-19, the number of inpatient cases in B.C. hospitals has increased by only four per cent — far slower than the province’s general population and its population of seniors.

But the patients that do arrive are lingering in hospital for much longer. The number of inpatient days has increased by 16 per cent since 2018-19, according to the data provided to The Tyee.

A major part of the challenge lies in the number of patients in hospital who don’t actually need hospital care, but are awaiting other means of care. Such “alternate level of care” patients account for between 10 per cent and 15 per cent of all acute care users in B.C. Most often, such patients are seniors waiting for space in an assisted or long-term care home. Others may be waiting for care to be organized in their own home or in a rehabilitation facility.

Osborne said the province has made some strides towards addressing the issue, pointing to newly opened long-term care homes, and improved primary care options facilitated by new urgent care centres and pharmacists with the ability to provide expanded care.

Unfortunately, those efforts have not yet moved the needle. In the two subsequent stories in this series, we will take a deeper look at the causes of B.C.’s perennial hospital capacity challenges, and the consequences of those capacity challenges for patients.

— This article was originally published by The Tyee. Article written by Tyler Olsen, The Tyee’s senior editor, and Michelle Gamage, The Tyee’s health reporter.

News from © iNFOnews.ca, . All rights reserved.

This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.