Elevate your local knowledge

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Sign up for the iNFOnews newsletter today!

Selecting your primary region ensures you get the stories that matter to you first.

The majority of British Columbia’s hospitals are consistently operating over 100 per cent capacity, which is affecting how well doctors can care for their patients in emergency departments.

As The Tyee reported Monday, at B.C.’s seven most overcapacity hospitals, at least one in six patients is being cared for in unfunded “surge beds,” often in hallways and other inappropriate spaces. These patients are at an increased risk of developing delirium and other negative health outcomes.

Hospital overcapacity also negatively affects emergency departments, which get backed up because their beds are occupied by patients waiting to be moved to hospital wards for care or treatment. This has a cascading effect on new patients waiting to be seen by a doctor in the emergency department; they often endure long wait times and sometimes give up and leave without being seen.

So: why does B.C. find itself in this situation? It’s because the province shrank its acute care capacity in the 1990s instead of maintaining and increasing it in anticipation of its population getting older and sicker, several experts told The Tyee.

’90s-era funding cuts

Today’s problems are the result of downsizing in the late 1980s and 1990s, when provinces and territories slashed the acute care capacities of their hospitals by around 30 per cent, according to Dr. Alan Drummond, who has worked as an emergency physician in Ontario for four decades. During his career he also sat as the public affairs co-chair of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, where he kept tabs on issues affecting doctors across the country.

Starting in the late 1980s, health care started to shift from inpatient care to outpatient care as hospitals cut back on extended care.

In the early 1990s, provinces such as B.C. were scrutinizing their health-care costs and determining they had more doctors and hospitals than they needed.

When Prime Minister Jean Chrétien was elected in 1993, he began reining in federal deficits by, in part, cutting health-care contributions to provinces such as B.C. B.C., in turn, responded by making policy changes to reduce what it saw as excess health-care costs.

One such cost? Excess hospital capacity.

In 1992-93, B.C. had 112 hospitals open. In 1993, B.C.’s population was around 3.6 million, with 13 per cent of the population considered senior, at older than 65 years old.

Statistics Canada calculates the median age in B.C. in 1993 at 35, but this number might be slightly off, as data from that year lumps everyone aged 90 to 100 into the same data category.

Reducing hospital capacity meant there were fewer beds available in hospital wards for emergency department patients who needed to stay overnight, Drummond told The Tyee. This made it harder for hospitals to deal with patient surges, like during a particularly bad cold and flu season.

Aging patients, aging caregivers

Today, B.C. has 113 hospitals open. Its population is 5.7 million, and 20 per cent of the population is aged 65 and older. Its median age is 41.

The average person will use the most health-care services between the ages of 60 and 90, and will generally have more complex health needs and take longer to recover, said Dr. Jeffrey Eppler, an emergency physician who has been working at Kelowna General Hospital for three decades.

Health-care advancements mean the average person is living longer, but that also means they need more health care as they age, he said, adding that at an average shift at Kelowna General, around half of the patients being admitted to the emergency department are 80 and older.

The City of Kelowna didn’t build out its hospital capacity to meet the demands of the aging population, despite the city doubling in size over the span of his career, Eppler added.

Older patients can get stuck in hospital beds while they wait for a bed in a long-term care facility to open up, Drummond said. These patients are referred to as “alternate level of care” or ALC patients.

ALC patients no longer need hospital care but aren’t well enough to be discharged home.

Many ALC patients are seniors with cognitive decline whose family or spouse is no longer able to safely care for them. There are 7,000 seniors who are waiting an average of 290 days to get into long-term care.

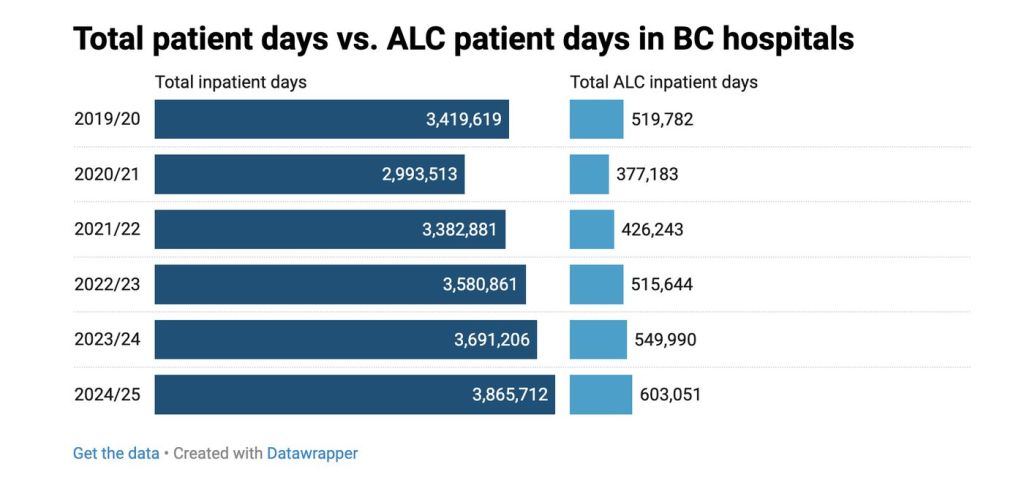

For 2024-25, the ALC rate for all hospitals across B.C. was just under 16 per cent, which is equivalent to about 1,600 beds, the Health Ministry said.

The ALC rate is calculated by comparing how many days all acute care beds in B.C. were taken up by ALC patients, out of how many days all patients in B.C. spent in acute care beds or rehabilitation beds in a given year.

Five years ago, the ALC rate was around 15 per cent. This number dipped closer to 13 per cent at the start of the pandemic as the province cleared out hospitals to make room for COVID-19 patients. As the acute infection stage ended, the ALC rate rose to 14 per cent in 2023 and 15 per cent the next year.

For example, at the qathet General Hospital, 10 of its 42 beds are occupied by seniors waiting for a bed in a long-term care facility.

The ministry said there is no industry standard or benchmark for ALC rates because different hospitals serve different populations.

To help reduce the ALC rate, the ministry told The Tyee, B.C. is investing in primary care and community-based services such as home health, long-term care, assisted living and respite services.

A sicker population

B.C. hospitals had been dealing with capacity problems for decades when the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Broadly speaking, the COVID-19 pandemic made the general population sicker, Damien Contandriopoulos, a professor in the school of nursing at the University of British Columbia, told The Tyee.

Patients who have had one or more COVID-19 infections are more likely to be suffering from metabolic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and autoimmune diseases today, Contandriopoulos said.

COVID-19 will continue to circulate and affect people’s health because the government is not requiring masking or ventilation in hospitals or schools and the province has not declared the disease as airborne, he added.

The health impacts of diseases like COVID-19 are further exacerbated by the shortage of family doctors in B.C.

People who don’t have family doctors wait longer to access health care, and by the time they finally go to a hospital their once-treatable condition has become chronic, Contandriopoulos said.

“By the time they’re getting treated they have late-stage cancer or additional problems,” he said.

Patients who are unhoused or use drugs or alcohol will also have more complex care needs, he added.

Staffing shortages

When hospitals are over capacity, staff workload increases while patient satisfaction drops.

Nurses face high rates of violence, abuse and punishingly high workloads, on top of taking the brunt of patient frustration related to health-care delays.

Veteran and green nurses alike are being pushed out of hospitals or out of health care altogether because going to work is like “a war zone” with no end in sight, Contandriopoulos said.

Health-care worker shortages can reduce how many acute care beds a hospital has available, as patients require both a physical bed to rest in and a health-care team to attend to them while they are in that bed.

B.C. turned to agency nurses as a stopgap measure to fill staffing shortages during the pandemic. Today agency nurses can make up the majority of nurses on a hospital floor, Contandriopoulos said.

Agency nurses work for private, for-profit agencies, who then contract them out to work for health authorities, rather than working directly for a public employer.

Agency nurses can often negotiate higher pay and more control over where they work and their schedule, for example declining overtime or night shifts.

The BC Nurses’ Union has criticized the government’s reliance on agency nurses and says the money on agency nurses would be better spent on long-term recruitment and retention strategies for public nurses. The more money the government spends on agency nurses, the less money it has to spend on public nurses, which affects long-term retention, the union says.

Hiring agency nurses is a “self-inflicted wound on the system,” Contandriopoulos said. The province gets stuck paying agency nurses more, which incentivizes more public nurses to quit and return as agency nurses, further driving up health-care costs.

A way forward

Experts recommended investments in several areas to improve hospital capacity and reduce patient bottlenecks.

Canadians will have to likely shoulder higher taxes to pay for more health care to ensure there’s a dependable, high-quality health-care system in place, Contandriopoulos said.

“We’re lying to ourselves if we say we can have a good health-care system without investing in it,” he said, adding that the alternative is to watch the system continue to crumble.

Governments will also need to invest in building more hospitals and increasing hospital capacity to keep pace with population growth, Eppler said.

To improve hospital capacity, governments should also build more long-term care facilities and recovery hospitals to move ALC patients to, he said.

Health ministers and hospital administrators should be held accountable if a hospital has to operate over capacity, Drummond said.

A national health-care approach could set parameters around access to health care, and if a hospital can’t deliver, then someone should lose their job, he added.

— In Part 3 of this series, The Tyee will take a deeper look at how hospital overcapacity affects patients and health-care workers.

— This article was originally published by The Tyee

— Article written by Tyler Olsen, The Tyee’s senior editor, and Michelle Gamage, The Tyee’s health reporter.

News from © iNFOnews.ca, . All rights reserved.

This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.