‘It almost broke me:’ For Okanagan, Kamloops cannabis retailers it’s been a tough 7 years since legalization

Vernon cannabis store owner Kevin Demers doesn’t sugarcoat it when he reflects on the last seven years of running his business.

“It almost broke me,” Demers told iNFOnews.ca. “I didn’t ever expect it was going to be easy, but certainly I didn’t think it was going to be this difficult.”

Demers’ comments come as Canada marks seven years, almost to the day, since marijuana was legalized on Oct. 17, 2018, making it the second country in the world to do so.

For the two years before cannabis legalization, Demers was running a highly successful cannabis dispensary. After 20 years in the oil and gas industry, it was quite the change from his previous career and when legalization came along he had high hopes for the next chapter of his business, Blended Buds Cannabis.

“Expectations were that we’d be able to expand our brand and get more products out to people,” the store owner said.

The reality was very different – his new store opened in a vastly different regulatory regime under legalization. There was far less product and far more restrictions.

“The first few years made it extremely difficult to stay in business,” Demers said.

After waiting a year for his final licence approval, he put cannabis on the shelves of his store in October 2019.

And he doesn’t pussy foot around when he compares the two businesses.

His old store, Hemp and Wellness, had 19 staff and was open fewer hours. His new one has just two employees.

“There was a good year and a half when it was just me 24/7,” he says.

He said his old store made about 500% more profit than Blended Buds.

He’s lucky he made it, as many others didn’t.

Stores grappled with long waits for licences, while their monthly rent was also due. The goal posts also moved. Vernon council put in a moratorium on cannabis stores downtown in the midst of some who had signed leases and were patiently waiting for provincial approval. They had to fight to get the rule overturned.

A few years after legalization, Vernon had 16 cannabis stores – a pot shop for every 3,750 residents.

In the summer of 2020, iNFOnews.ca reported that Vernon had more cannabis stores than any other mid-sized BC city.

The market was clearly saturated, and now, seven years since legalization a quarter of Vernon’s stores have since closed down.

Across the Thompson and Okanagan regions, there are currently 88 legal cannabis stores, and the storefront industry appears rather flat.

In 2020, Kelowna had eight stores, and two years later that number had jumped to 18. But by 2024, it was down to 16 pot shops. Somewhat surprisingly, the city rebounded, and there are currently 20 pot shops in Kelowna, plus five in West Kelowna.

The City of Kamloops has shown a similar pattern, going from 12 in 2020 and increasing by a third in 2024 to 16 stores. One had since closed down, leaving 15.

And based on provincial numbers, it seems unlikely that many more stores will open in the near future. In 2019, British Columbia had 185 cannabis stores, which by 2022 had more than doubled and jumped to 491.

However, since then, fewer than 40 cannabis stores have set up shop around the province.

Across the country, Canada went from having 210 stores in April 2019 to 3,500 by April 2023.

It’s unclear how many BC stores haven’t made it, but in Ontario, by late November 2024, one-fifth of stores had already shut down.

The numbers don’t account for the dozens of unlicensed cannabis stores found on Indigenous reserves around the province.

In the seven years since cannabis was legalized, the industry has had its ups and downs.

Some thought the legalization would trigger an economic gold rush, while others thought it would be a public health nightmare.

However, neither statement appears to have been correct.

According to Statistics Canada, cannabis use was steadily growing among the population years before legalization. Between 1984 and 2017, cannabis use grew from 6% to 15% of the population.

And young people didn’t pick up the bong as soon as the government legalized it.

A recent McCreary Centre Society report found the number of British Columbian teens who had tried cannabis dropped to 22% in 2023, down from 41% in 1998. However, the number of teenagers who smoked cannabis more than 20 days a month increased to 18% in 2023, from 11% in 2018.

And 12% of the teens surveyed in the Okanagan smoked cannabis every day.

Demers estimates that about one-third of his clientele are seniors, and another third are over 40.

Whether cannabis legalization triggered an economic gold rush depends on who you are.

According to a Deloitte report released this year, the cannabis industry generated $76.5-billion in GDP and $28.7-billion in sales between 2018 and 2024. It has also generated $29.6 billion in government revenue and employs close to 100,000 Canadians.

Not everyone is seeing huge returns on their investment.

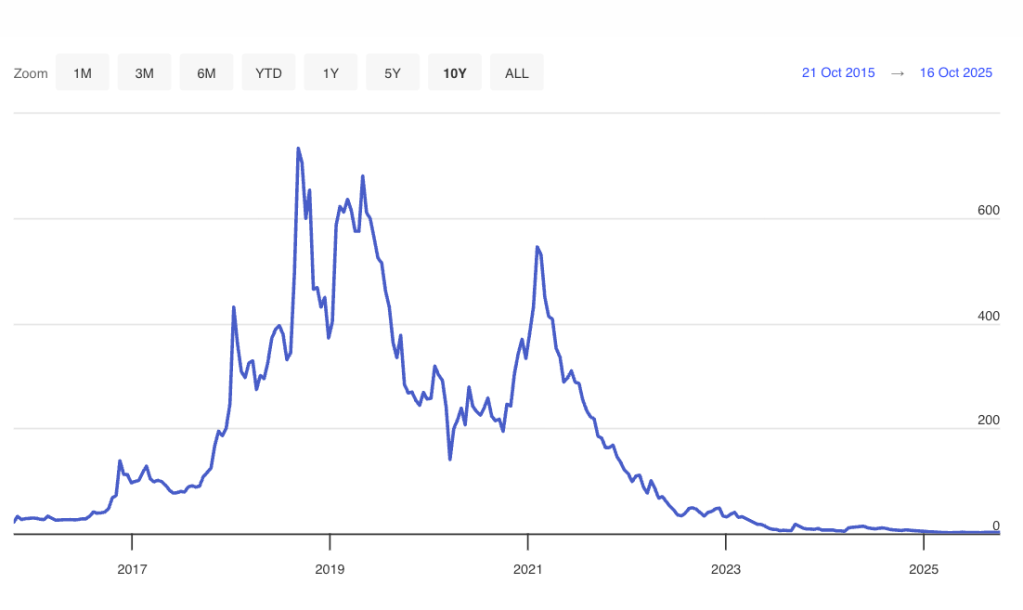

Canadian cannabis companies listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange currently have share prices a mere fraction of what they once were.

In late 2022, Kelowna-based cannabis company Flowr was given creditor protection after having debts of more than $7 million. Run from its Toronto head office, the company had an 85,000-square-foot site on McCarthy Road on a 25-year lease, employing 80 staff.

Its 2021 financial statements showed it had losses of $92 million, bringing in revenue of $12.3 million. In a court filing, the company blamed an oversaturated market, saying cannabis licences went from roughly 100 at legalization to 800 by 2022.

Canopy Growth once had the largest indoor cannabis production facility in Canada when it took over a shuttered Hershey chocolate building in Ontario in 2017. Fast forward six years, and the company has sold the building.

The company recently announced it would repurpose its Kelowna facility for medical cannabis, moving away from the recreational market.

In 2016, its share price hovered around $25 and peaked in October 2018 at $766. It’s now worth $1.92.

South Okanagan resident and former Olympic snowboarder Ross Rebagliati was once part of what Bloomberg called the ‘Dot-Bong’ boom.

In 1998, Rebagliati made headlines for winning gold in the men’s giant slalom event at the Winter Games in Japan, only to lose it after testing positive for marijuana, and then to get it back days later following an appeal.

Turning that notoriety around, after retiring from snowboarding and years before legalization, Rebagliati launched Ross’ Gold in 2012.

“We had a line of bongs and glass pipes… and different things for consuming cannabis, but at the time we didn’t have any cannabis,” Rebagliati told iNFOnews.ca.

Regardless of the company’s lack of cannabis or a legal market, there was a lot of excitement in cannabis stocks and venture capital available, he said.

His company went public, and the stock skyrocketed.

A 2014 Bloomberg article put Ross’ Gold market value of $38.4 million and with Rebagliati having 49% of the shares, his stake was worth about $18 million.

However, financial regulations meant he couldn’t just sell the stock and it was soon back to zero.

“I was kind of new to the whole thing at the time… I came from the world of sports, so it was a big learning curve,” he said.

He dissolved the company after that and then rebooted it after legalization, just as a brand.

“We just took a couple of years off just to… watch what happens and learn from our experience,” he said.

He now makes licensing agreements with certain producers and has the Ross’ Gold brand on several products. He’s also started a pre-roll manufacturing facility.

While Rebagliati has used his brand to grow his business, one aspect of the industry which is different from most is that government rules mean stores and companies aren’t allowed to advertise.

Kelowna weed store manager Julia Beck has been with the Cannabission store since just after legalization and said not being allowed to promote and advertise has been one of the hardest hurdles in growing the business.

“We can’t technically advertise or promote it anywhere, especially outside of the store,” she said. “We have to be very cautious of how we present (cannabis) in store and then also how we word things as well. You have to be extremely specific and careful and cautious when trying to come up with these things.”

It makes growing a business difficult.

“So the most important thing is that we carry a good reputation. Our customer service is as high as possible (and we) get as many great reviews as we can, she said. “That’s how I find we’ll gain new people.”

Speak to anyone working in the cannabis industry, and they’ll complain about the amount of government regulation surrounding the industry.

South Okanagan resident Jaimie Miller started working as a budtender after legalization and now works as an independent sales rep for several cannabis brands.

She had high hopes about legalization.

“I had great expectations that we would have an industry that operated just like the wine industry, where consumers could go and visit the location where the plants were grown and processed and such, and we’d be able to have some kind of cannabis tourism by now,” Miller said. “That’s been farthest from what’s happened… It’s been the opposite of what I thought it was going to be like.”

Taxes and red tape are major sticking points for those trying to navigate working in the cannabis industry.

She said the provincial government isn’t listening to business concerns, and while she’s tried to lobby for the cannabis industry, it’s not easy.

“We’ve been screaming into the void since the very beginning… politicians aren’t going to win their seat based on a cannabis-related argument,” Miller said. “We’ve been saying the same thing for seven years… and absolutely diddly squat has happened to alleviate any of those problems.”

Back in Vernon, Demers is quietly optimistic about the business.

When he opened, he only had 300 products on the shelves. Now he stocks about 1,400. The exorbitant business licence fee charged by the city is gone and he’s now on par with other stores, and the mandated frosted glass has disappeared so people can now see in. He’s allowed to purchase directly from small producers, key especially during the BC General Employees’ Union strike, which closed cannabis distribution centres.

The weed industry does seem unfairly picked on, taxes that cost the liquor industry 3.5%, cost the cannabis industry 15%. And doing the paperwork is a full-time job alone.

Prices are also at their lowest in seven years.

A 2017 Public Safety Canada report found that pre-legalization, a gram of cannabis cost between $7.14 and $7.69 per gram depending on quality. A gram can now be bought for as little as $2.86.

“It’s all a race to the bottom in pricing for Canada right now,” Demers said. “But margins are the same.”

As cannabis prices drop and business expenses increase, it’s squeezing those in the industry very tightly.

“You have to be the lowest priced in town if you want to be competitive. Which makes it hard to run a business,” he said.

While he says it’s pure speculation, Demers estimates the black market still accounts for 20% of the market.

The “grey market” of unlicensed pot shops on Indigenous reserves has also had a huge effect on business.

He doesn’t regret getting into the cannabis market but isn’t shy to say it’s been very difficult.

“Knowing what I know now, would I have done something different with my investment dollars and time? Probably… I don’t regret it because I can see it turning now… there’s still time for it to pay off,” he said.

News from © iNFOnews.ca, . All rights reserved.

This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Join the Conversation!

Want to share your thoughts, add context, or connect with others in your community?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

2 responses

This is a test comment

This is still a test comment